Building Community

Whether you’re interested in learning more about Victoria’s heritage homes or you own one yourself, VHF has the resources to answer your questions.

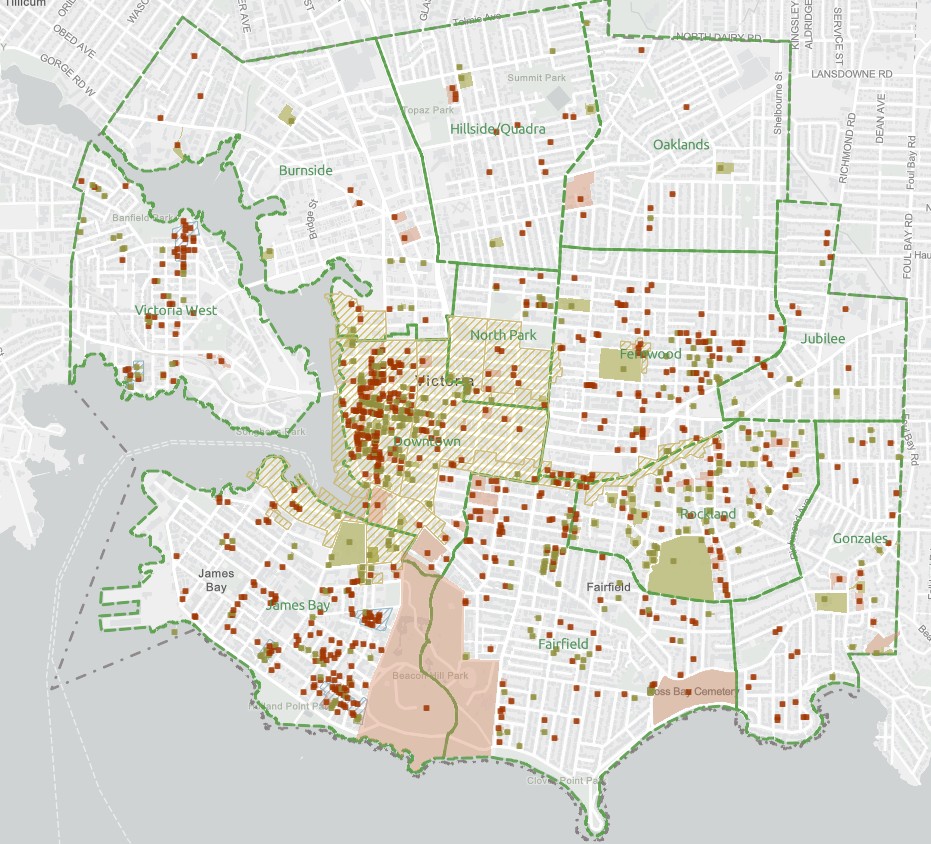

GIS Map

Explore VHF’s award-winning Heritage Properties GIS (Geographic Information System) map. Click on the map to open a larger version with more layers and functions. In the map you can activate or disable layers from the dark sidebar on the left, allowing you change basemaps, or zoom into the aerial photo.

Move around the map, zoom in and out, and click on the icons to learn more about the properties on the City of Victoria’s Heritage Register. This will open a pop-up box with additional information for each property including links to a photo and a more detailed description.

Although not covered in the Victoria Heritage Foundation’s This Old House series, Downtown commercial, industrial, institutional or apartment Heritage Register properties are included with links to their Statement of Significance on the British Columbia Register of Historic Places, where available.

Click the Map

By William R. Muir

Drawings by Cecilia Mavrow

The primary purpose of a house is to provide shelter from the elements. But few homeowners are content with a building that just keeps them warm and dry; most want a home that is aesthetically attractive and that provides the viewer with a favourable impression of their social status. Throughout much of Victoria’s early history people have felt that a “styled” house, one whose shape, materials, detailing, or other features conform to a current architectural or social fashion, would do just that. Styles frequently begin when a creative architect devises an innovative house pattern that quickly catches local interest. It will spread when other architects consult the professional literature to keep current with national and international developments in building styles; professional builders often use pattern books of building plans that are currently popular.

Some styles have arisen from an attraction to buildings considered typical of a particular historical time and place. Ancient Greece and Rome, for example, have provided models for homebuilders during several periods, generally referred to as the Classical Revival Movement (“Revival” is used here to indicate that a style from an earlier era is being recreated). For some this was because of nostalgia for what was considered to be a superior way of life at that time, which might be emulated today by imitating its architecture. For others the buildings of that era were intrinsically attractive and needed no ideological justification for copying.

Other styles have emerged because a particular abstract preconception of attractiveness such as “symmetry” or “use of natural materials” has been generally agreed upon. Sometimes this type of style can coexist with or emerge from a historical style; for instance, one of the characteristics of Classical Revival houses is that they are usually symmetrical, and symmetry can remain a valued characteristic of a building long after people stop consciously copying Greek and Roman models.

However, the popularity of a particular style at a particular time has often been governed by factors other than aesthetics and domestic comfort; politics and ideology frequently played a role. This point will be further elaborated in the discussion of individual styles.

Folk or Vernacular

×

Not all houses are designed according to the latest mode. Some homes, typically built by their owners or by small-scale or nonprofessional builders, show little concern for changing fashions. The criterion for the choice of design of such houses is more likely to be the cost of construction or local architectural traditions. In this book houses that do not conform to a generally recognized style that occurs outside Victoria will be termed vernacular, or as a house form or type. Even so, these buildings have often obviously been influenced, directly or indirectly, by some conventional style. Vernacular buildings that contain some features associated with a standard style will be identified as such.

Colonial Bungalow / Classical Cottage

One house type frequently seen in Victoria that can be considered a vernacular style is the single-storey, hipped-roof cottage or bungalow. An important attraction it offers is economy: it provides the most space for the least money of any building shape. It has been suggested that this style was inspired by a building found by British colonial administrators in India called a bangla, resulting in its being named a Colonial Bungalow.

This 1½ storey, bellcast hipped-roof cottage built in 1911 at 614 Seaforth (Vic West) nicely demonstrates the basic features of the Colonial Bungalow. Many examples of this type have only attic space under the broad-eaved roof with a single dormer to light it, but this house was designed with second-storey living space, complete with generous dormer windows and a sleeping porch. A full-width front porch is sheltered under the house roof. The Tuscan Classical Revival columns supporting the porch are a sign of its being built in the Edwardian era.

There are other possibilities for the inspiration of single-storey, hipped-roof house-types in Victoria, such as similar houses observed in French North America or the Ontario Classical Cottage of the 19th Century. Classical Cottages generally have a smaller, more formal entry porch. They often have features borrowed from the dominant style of larger houses at the time they were built: the Italianate cottage typically has eaves brackets and a front angled bay window balancing the entry porch, both with hooded roofs, while if it has turned “gingerbread” porch supports and prominent, asymmetrically placed, pedimented bay windows it would be called a Queen Anne Cottage.

Classical Revival

×

Modern western civilization has long recognized that its roots lie in the cultures of classical Greece and Rome, and there have been several architectural movements based in some part upon emulating buildings of ancient times. Sometimes this has been manifested as a direct copying of Greek or Roman buildings. Other styles have been based on designing buildings according to the same rational principles used by classical architects, such as symmetry, balance, and proportion.

In addition to the specific styles it produced, the classical movement also contributed eclectic elements to other different styles. This was particularly the case in the period from around 1900 to 1914, when many houses became simpler and more symmetric, and made use of ornamental dentils and columns. This is sometimes referred to as the Edwardian Classical Revival.

Neoclassical Style

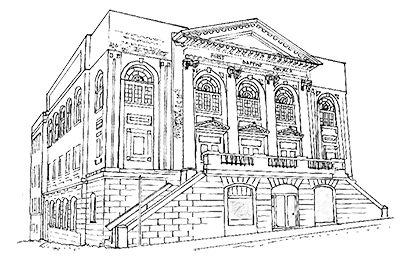

The World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, widely publicized several impressive buildings based on classical themes, and inspired many similar architect-designed buildings in the United States and (to a lesser extent) in Canada over the next half-century. Only a few examples of these are seen in relatively pure form in Victoria, mostly in commercial or institutional buildings. Typically there is a domination of the façade (and sometimes the sides) of the building by a porch that appears to have been taken from a Greek temple. Although the bulk of the building may obviously be a different style, it is usually symmetrical and may have classical details.

Neoclassical

This building at 1600 Quadra (North Park), designed as the First Congregational Church in 1913, is a symmetric brick building fronted by two-storey Ionic columns supporting a wide frieze and a triangular pediment. Classical details are the modillions under the eaves and dentils on the cornice, and the three triangular pediments above the entrance doors.

Homestead Style (Vernacular)

The first North American interest in classical buildings occurred from around 1770 to 1860, after the American Revolution when the republican concept of Rome fired the public imagination in the United States and suggested an architectural model, first for public buildings and then for homes. Well-known examples are the Gone with the Wind columned mansions built in the southern states before the Civil War. This was too early to directly affect developments in Victoria. However, numerous simpler vernacular approximations to these houses were subsequently built throughout North America, particularly in rural areas, and remained popular long after the demise of the formal style. The type ultimately became a favourite for inexpensive working-class houses built on narrow city lots. They are typically 1½ or two storeys tall, with a front-gabled roof and a porch that can be recognized as approximating the form of a Greek temple. For this reason they are also called Temple Houses.

Homestead Style

It is doubtful that the builders of this 1892 house at 2011 Cameron (Fernwood) were thinking of a Greek temple when it was constructed, but its similarity to mid-19th-Century houses that were designed on classical models is clear. It is close to symmetric and has a modestly pitched front-gabled roof, in this case with an incomplete pediment and cornice returns. There is a board frieze under the eaves, while cornerboards represent pilasters. The porch even has three square supports approximating Corinthian columns with stylized fretwork foliage in the capitals.

Georgian Revival Style

Another architectural style based on principles of classicism was Georgian, which began as a favourite for British stately country homes. A few vernacular Georgian homes (for example, Craigflower Manor in View Royal) were built by pioneers in the Victoria area. However, the only surviving examples of the style within Victoria date from the beginning of the 20th Century, when it enjoyed a revival of interest that has continued to this day.

The original Georgian houses were designed by British architects influenced by the classical principles of balance, symmetry, and simplicity as they perceived them in Italian Renaissance buildings. The classic Georgian house is a simple, two-storey, rectangular box with a hipped or side-gabled roof, and door and windows symmetrically arranged on the front façade. It typically has five double-hung sash windows on the top floor, and a central door and four windows at the ground level. The front entrance is the focal point of the façade, drawing the eye by being the most elaborately decorated feature of the house, projecting forward in a gable, or being enclosed by a porch. There are often classical features such as columns, pediments, modillions, or dentils on the house.

Georgian Revival

This Georgian Revival home at 1509 Rockland (Rockland) was built in 1922. Like most Revival houses it deviates somewhat from the original Georgian style: it has one window too many on the top floor. Apart from that it has many of the relevant features, such as symmetry, classical pediments on the dormers, and a door enclosed by a pedimented porch with classical columns. Most Georgian Revival houses in Victoria deviate even further from the norm with features such bay windows, multiple windows, and off-centre doors, not found on original Georgian models.

Romantic or Picturesque

Around the beginning of the 19th Century there was a reaction to the principles of Classicism, intellectual assumptions such as the appeal of simple symmetric structures determined by geometric rules. Instead, a new movement called Romanticism proposed aesthetic standards based on how buildings arouse emotional reactions in the observer (a similar development in music occurred when composers such as Tchaikovsky and Wagner moved away from the music of Bach). Such houses are often called Picturesque because their appearance was considered appropriate to be the subject of a painting. The Romantic or Picturesque styles were inspired by the architecture of particular historical periods, although they were often not very accurate copies of buildings of those times.

Gothic Revival Style

Gothic Revival

The first Canadian buildings in the Gothic Revival style were churches built at the beginning of the 19th Century, when it became considered as appropriate for religious and public buildings because of its associations with medieval European Christianity. It had earlier been used in England for grand country houses, and from there became popular for residences in the United States and Eastern Canada from about 1840 to 1865. Originally a style designed for masonry buildings, it was adapted to frame construction in a form called Carpenter Gothic for simpler homes. In Victoria it is mainly seen in churches and in residences originally built in country settings in the 1860s, although a few later examples can be found. Typical Gothic features are steeply gabled roofs with cross gables, elaborate carved bargeboards, flattened arches in porches, and pointed-arch windows (or rectangular windows with frame mouldings giving that effect) often extending into the gables.

Wentworth Villa was built at 1156 Fort (Fernwood) around 1862 in Carpenter Gothic. It is typical of how the Gothic style was applied to a modest residence with its steep side-gabled roof, centred wall-gable in the front façade, and intricately carved bargeboards. The wraparound porch with its support brackets simulating a flattened arch, and the token ornately detailed pointed window set prominently in the peak of the wall-gable, are examples of how an otherwise simple house could be transformed into a recognizable style.

Italianate Style

Houses based on Italian models were very popular in Victoria from 1860 to the turn of the 20th Century. Many of the first residences constructed on extensive estates outside town were inspired by the informal villas of the Italian countryside and were given the label “Italian Villa” style. These were rambling, two-storey structures, their low-pitched, gabled roofs frequently having widely overhanging eaves with decorative brackets beneath. They had tall, narrow windows with arched tops or hoods above them. The earliest examples had a prominent front-facing gable; a few later ones had a tower, almost always in the angle of two wings of the main building (rather than at a corner, as in Queen Anne houses).

Fairfield at 601 Trutch (Fairfield) was built in 1861 on an estate that would later become the neighbourhood of that name. It is a frame building, with rectangular windows topped by hoods, unlike the segmentally arched ones typically seen on stone or brick houses.

A second Italian house style that proved attractive in early Victoria was the Cubical Italianate. This was a severe, two-storey, symmetrical, box-shaped building with a hipped roof and bracketed eaves. The originals were always stone, brick, or stucco, and usually had arched windows, belt courses, and corner quoins.

Italianate Style

Built in 1860 (and demolished in the 1960s) on a country estate that was later subdivided to become the neighbourhood of the same name, Fernwood was a good example of Cubical Italianate. It had a simple entry porch with square supports and a flattened arch.

Although the Italian Villa and Cubical Italianate forms were easily distinguishable in the 1860s, subsequent builders frequently built houses that were a composite of the two types that became known simply as “Italianate style.” Houses with several wings had hipped roofs, 1- or 2-storey bay windows were often added, and Classical Revival features such as triangular pediments on gables became common. At the end of the 19th Century many simple box-like structures were made stylish just by the addition of some eaves gables and window hoods. To complicate things further, many builders of Queen Anne houses added Italianate features, so that assigning a single style becomes debatable for many houses.

Second Empire (Mansard) Style

This style reached North American notice because of its part in the extensive building program undertaken during the reign of Napoleon III (1852-1870), France’s Second Empire. So although it had its origins in the French Renaissance, it was perceived at the time as being a modern and very up-to-date introduction, in contrast to the Romantic and historic nature of the revival styles. Perhaps for this reason it was short-lived – it was used in Victoria for four public buildings in the period 1875-1882 (the Customs House, City Hall, the Masonic Temple, and the now-demolished Central Boys School) and a handful of surviving residences built around 1890.

Second Empire

The distinguishing feature of Second Empire is its mansard (dual-pitched) hipped roof that changes from a steep to a shallow angle. The steep portion of the roof can be straight, or curved in complex ways, and typically will have dormer windows in it. The remainder of the house is usually very similar to an Italianate home. A classic example of a Second Empire house, Trebatha at 1124 Fort (Fernwood) was built in 1887. Its roof begins with a flare and then straightens, topped with a shallow hip. The rest of the building is indistinguishable from a Cubical Italianate house with its narrow double segmentally arched windows.

Queen Anne Style

This style is the epitome of a Picturesque building style. Supposedly inspired by the architecture current during the reign of Queen Anne (1702 – 14), the concept was in fact created by a group of British architects in the 1860s working from late medieval models, which also provided inspiration for the Gothic and Tudor Revival styles and the Arts & Crafts movement. The first Queen Anne built in Victoria beginning in the 1880s represented this British school. But the style was modified south of the border to a more flamboyant architectural expression (typically with a wraparound entry porch decorated with spindlework), and the 1890s saw several still surviving homes built in a more North American mode. In Victoria the style was also frequently modified with Italianate elements, and in its dying days in the first decade of the 20th Century (Edwardian Era) Classical Revival features were often added.

This style was the antithesis of the simple, symmetric Classical approach. Victoria’s typical Queen Anne house has a steep hipped roof and two or more gables projecting irregularly, although a few are front-gabled. More elaborate dwellings will have a tower, usually octagonal or round, projecting from a front corner. The defining characteristic, however, of the style is its variety of surface treatments – a Queen Anne house will use almost anything to avoid a smooth-walled appearance: pent roofs, cutaway bay windows, projecting gables, half-timbering, patterned shingles, terracotta tiles in brickwork.

Roslyn (1135 Catherine, Vic West: drawing from photo courtesy CVA PR252-7098) also dates from 1890, but illustrates how the style had developed after being imported to the United States; this house was built from a mail-order plan by American architect G.F. Barber. On the porches it shows the feature most popularly associated with the Queen Anne style, spindlework. It also demonstrates many of the elements used to avoid flat wall surfaces: projecting gables, pent roofs, horizontal siding, and a variety of shingle patterns.

This is a picture of 223 Robert (Vic West), built in 1903-04. It has many typical features of the late Victorian Queen Anne style such as the fancy shingles and pent roof in the gables, the cutaway bay windows, and the Italianate brackets under the eaves. However, the beginning of the transition to the Edwardian period is marked by touches such as the discreet narrow beveled siding and Classical Revival features like the Tuscan columns on the porch. Smaller single- or 1½-storey versions are called Queen Anne cottages.

This style originated on the northeastern coast of the USA, principally in vacation residences in fashionable resorts, and inspired several Victoria homes and churches at the end of the 19th Century. The defining feature of a Shingle building is wall cladding of continuous wooden shingles, almost like a skin, which unifies the irregular shape of the house within a smooth surface. They often have substantial masonry foundations or ground floors. Their roofs are typically steep and may be gabled or hipped with cross-gables (like the Queen Anne), and like that style they are usually rambling, asymmetric buildings. They also frequently have corner towers, usually integrated bulgelike into the body of the house, rather than attached as distinct structures. The classic examples of the style emphasize the horizontal lines of the building, strips of multiple windows often contributing to this impression. Shingle buildings often also incorporate Romanesque arches and Classical Revival details such as Palladian windows.

This house built in 1896 at 1032 McGregor (Rockland) is based on what appears to be a rubble stone foundation, above which it rises like an irregular pile of simple geometric forms, all bound together by a shingled casing. Window surrounds have little decorative detail, and the continuity of the surface has minimal interruption from features such as corner boards and stringcourses. A multiple string of windows runs around the top of the tower and across the overhanging gable in an attempt to counteract the vertical impression given by the building’s sitting on the brow of a hill.

Arts & Crafts

This was not as much a style as an ideological movement, although the Victoria architects who were influenced by it left a recognizable mark upon the local landscape. The Arts & Crafts movement is most simply summarized as one initiated by a group of British artists and architects reacting to several features of Late Victorian life, principally the dehumanizing effects of industrialization and the unquestioning imitation of earlier formal historical styles. Rather, they espoused architecture that showed evidence of human handiwork, that was functional, and that respected British vernacular traditions of house building. Ironically, their admiration of the vernacular meant that they often incorporated elements from medieval buildings in their work that were also copied by the proponents of the Gothic, Queen Anne, and Tudor Revival styles that they criticized. As a result, it is sometimes difficult to discern the boundaries between these different styles.

Tudor Revival

Tudor Revival (also known as English or Elizabethan Revival) is a style that was created to evoke the spirit of traditional medieval English structures, particularly rambling country manor houses and rural cottages. The first examples were architect-designed stately homes in late-nineteenth century England that mimicked the appearance of growth through centuries of additions. Throughout the British Empire, and in Victoria in particular, this architectural style came to symbolize a traditional British way of life. There are a few instances in Victoria of homes similar to the original, historically inspired prototypes. However, most examples of the style here use it in eclectic mixtures. Many local architects (notably Samuel Maclure) used selected Tudor Revival elements in their designs, apparently to appeal to their clients’ Anglophile bents, but without attempting to create historically accurate copies. And a large number of more modest homes built in the first third of the twentieth century were modelled on medieval cottages in a subset of the style called English or Cotswold Cottage, which sometimes included an attempt to simulate a thatched roof.

Tudor Revival

The style is described here as a set of features frequently found in houses that are at least part Tudor Revival. The more features that appear in a given building, the closer it is to the style. Hatley Park, designed by Samuel Maclure, with Douglas James, and illustrated here, is possibly the purest version of Tudor Revival to be found in the Capital Region.

- steep, side-gabled roof

- one or more steeply pitched front gables, often asymmetric or overlapping

- decorative half-timbering inset with masonry (usually stucco) (This may also be found in the gables of Queen Anne and Arts & Crafts houses, which derive from medieval models as well. Half-timbered gables and walls usually indicate a Tudor Revival house.)

- entry with either no or a small porch, frequently with a flattened, pointed (Tudor) arch and quoin-like tabs of brick or stone projecting into the surrounding masonry

- oriel windows

- either rows of three or more casement windows, or tall narrow windows, often with multiple panes or leaded diamond glass

- jettied upper storeys (also indicative of Queen Anne and Arts & Crafts houses)

- massive chimneys on an outside wall, sometimes with multiple flues (This can be a feature distinguishing Tudor Revival from Queen Anne and other types of Arts & Crafts houses, whose chimneys are usually internal.)

- crenellated towers and bay windows

British Arts & Crafts

The British Arts & Crafts concept was attractive in Victoria to “Little England” enthusiasts intent on recreating the homeland on Canadian soil. A large number of architects with appropriate backgrounds were available to oblige by providing house designs in this genre for upmarket clients. As the British models they worked from were diverse, so were the Victoria houses they produced; as well, individual architects added their own idiosyncratic touches to their work. But there is a common mood to these houses: although they look like they have just been plucked, steep-roofed and asymmetrical, from the English countryside, they don’t look out of place in a British Columbian suburb, particularly in terms of their building materials.

Brothers Douglas and Percy Leonard James, both trained in England, designed 1015 Moss (Rockland; drawing from photo, 1977, Hallmark Society), built in 1912-13. It is clad largely in shingle, but features many medieval British features such as half-timbered panels, leaded-glass windows, and oriel window on the side. The prominent gable on the left of the façade, with its recessed arch and two-storey bay window, looks as though it has come from an earlier Queen Anne, but there is no variety-for-variety’s sake in this house: it has an overall unity to it.

Edwardian Vernacular Arts & Crafts

This vernacular house type with strong Arts & Crafts features, although not unique to Victoria, seems to have been built here in larger numbers than anywhere else. Thousands were constructed during an economic boom between 1904-1914; fewer can be traced to before or after that period. Most were built by contractors such as David Herbert Bale, and do not seem to have been architect-designed, although it has been suggested that some of the houses of renowned Victoria architect Samuel Maclure provided a model for them.

The basic characteristics of this house are a height of 1½ storeys, with the second level designed for living space, and a front-gabled roof pitched at approximately 45 degrees, with the gable ends at the top of the main floor walls. There are typically one or two dormers, usually gabled. Half-timbering and dentil mouldings are often seen in the gables, and many have wide bargeboards with eave returns at the bottom. Earlier instances typically have closed eaves; later ones may have open eaves and exposed rafter tails similar to those in Craftsman houses. Almost all have an asymmetrical main floor on the front facade, with inset entry porch on one side of the façade and a bay window on the other, and a symmetrical upper level.

The façade of 1127 Fort (Fairfield) built in 1907, is suggestive of a gable on a Queen Anne house (which is related to the Arts & Crafts movement) in its multiple levels and surface treatments. The half-timbered gable and prominent roofline are reminiscent of several high-fashion Arts & Crafts houses based on a Swiss Chalet model designed a few years earlier by Samuel Maclure.

Craftsman Style

The Arts & Crafts philosophy was taken up in the United States by furniture maker Gustav Stickley in his magazine The Craftsman, where he made available plans for houses in that fashion for free; the magazine name subsequently became identified with the American version of the style. Stickley stressed the use of low, broad proportions, natural building materials, and the absence of artificial ornamentation in his houses. Two California architects, brothers Charles and Henry Greene, popularized Craftsman-style bungalows, and shortly after 1905 the style and house type became the dominant one for smaller American houses until the early 1920s; in fact, the style is frequently referred to simply as “Bungalow.” Many companies sprang up to offer building plans, full kits of building materials that could be shipped to the customer’s lot, or complete design and construction services to erect a house in this style. Many Victoria Craftsman bungalows, two-storey houses, and even a few Craftsman churches date from this period.

Craftsman buildings tend to differ from British Arts & Crafts structures in having lower-pitched roofs. Their ornamentation, although its medieval origins are discernable, is more stylized; almost all Craftsmans have open eaves with exposed rafter tails, many have decorative beams or triangular braces under their gables, and local examples frequently have some token patches of half-timbering. They are usually side- or front-gabled, and have a front entry porch: in simple examples this will be incorporated under the main building roof, while more elaborate structures will have a gabled or shed-roofed porch in front. The porches on many Craftsmans have square supports based on battered stone piers or shingled balustrades. Bargeboards on gables are usually wide and frequently are slotted and have pointed tips.

Craftsman Style

This house was built in 1911 at 20-24 Douglas (drawing from photo c.1913 from Craftsman Bungalow catalogue, courtesy Larry Kreisman) from Plan 327 designed by architect Jud Yoho of Seattle. Massive stone pillars support the porch; more commonly in Craftsman houses the stone would extend only part way up as a pier, and wooden supports would rest on them. The open eaves, exposed raftertails, and beam-ends with brackets under the gables are typical.

Foursquare (Vernacular)

A group of Chicago architects, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and known collectively as the Prairie School, originated a uniquely American house style at the beginning of the 20th Century. Many of these houses had low-pitched, hipped roofs with widely overhanging eaves, emphasizing horizontal lines. While this movement seems to have had minimal impact on professional architecture in Victoria, from houses scattered throughout the city there is ample evidence that builders, following their gut feelings on what clients wanted, were constructing scores of residences influenced by the style, presumably from the many pattern books available. Most date from shortly before WWI.

This house type is known as a Foursquare or Prairie Box. The basis of its appeal was in part functional – it is essentially a two-storey version of the Colonial Bungalow that had been an evergreen favourite for decades earlier because it was cheap to build. The introduction of platform frame construction would have decreased the cost of adding a second storey. In form it is also an expanded version of the Cubical Italianate that had been fashionable a generation earlier, minus the bay windows and eaves brackets, and plus some dormer windows on an expanded third level.

The classic Foursquare (so-called because it typically has four rooms on each level) is a hipped-roof cube with features that emphasize its horizontal lines: wide watertables, belt courses, and friezes separating levels of the building; contrasting materials at different levels; wide front porches; and multiple strings of windows. It usually has at least one dormer window.

Foursquare

This Foursquare at 123 Howe (Fairfield, not on City’s Heritage Registry) is a classic of the type. Its horizontality is accentuated by three bands of smooth boards girdling the house and separating the sections of rougher cladding, alternating claddings of shingle and bevelled siding, and contrasting colours for the different materials. All windows in the façade are in groups of three, there is a wide, low front porch, and the low front dormer further stresses the flattening effect of the bellcast roof.

By William R. Muir

Drawings by Cecilia Mavrow

The primary purpose of a house is to provide shelter from the elements. But few homeowners are content with a building that just keeps them warm and dry; most want a home that is aesthetically attractive and that provides the viewer with a favourable impression of their social status. Throughout much of Victoria’s early history people have felt that a “styled” house, one whose shape, materials, detailing, or other features conform to a current architectural or social fashion, would do just that. Styles frequently begin when a creative architect devises an innovative house pattern that quickly catches local interest. It will spread when other architects consult the professional literature to keep current with national and international developments in building styles; professional builders often use pattern books of building plans that are currently popular.

Some styles have arisen from an attraction to buildings considered typical of a particular historical time and place. Ancient Greece and Rome, for example, have provided models for homebuilders during several periods, generally referred to as the Classical Revival Movement (“Revival” is used here to indicate that a style from an earlier era is being recreated). For some this was because of nostalgia for what was considered to be a superior way of life at that time, which might be emulated today by imitating its architecture. For others the buildings of that era were intrinsically attractive and needed no ideological justification for copying.

Other styles have emerged because a particular abstract preconception of attractiveness such as “symmetry” or “use of natural materials” has been generally agreed upon. Sometimes this type of style can coexist with or emerge from a historical style; for instance, one of the characteristics of Classical Revival houses is that they are usually symmetrical, and symmetry can remain a valued characteristic of a building long after people stop consciously copying Greek and Roman models.

However, the popularity of a particular style at a particular time has often been governed by factors other than aesthetics and domestic comfort; politics and ideology frequently played a role. This point will be further elaborated in the discussion of individual styles.

Folk or Vernacular

Not all houses are designed according to the latest mode. Some homes, typically built by their owners or by small-scale or nonprofessional builders, show little concern for changing fashions. The criterion for the choice of design of such houses is more likely to be the cost of construction or local architectural traditions. In this book houses that do not conform to a generally recognized style that occurs outside Victoria will be termed vernacular, or as a house form or type. Even so, these buildings have often obviously been influenced, directly or indirectly, by some conventional style. Vernacular buildings that contain some features associated with a standard style will be identified as such.

Colonial Bungalow / Classical Cottage

One house type frequently seen in Victoria that can be considered a vernacular style is the single-storey, hipped-roof cottage or bungalow. An important attraction it offers is economy: it provides the most space for the least money of any building shape. It has been suggested that this style was inspired by a building found by British colonial administrators in India called a bangla, resulting in its being named a Colonial Bungalow.

This 1½ storey, bellcast hipped-roof cottage built in 1911 at 614 Seaforth (Vic West) nicely demonstrates the basic features of the Colonial Bungalow. Many examples of this type have only attic space under the broad-eaved roof with a single dormer to light it, but this house was designed with second-storey living space, complete with generous dormer windows and a sleeping porch. A full-width front porch is sheltered under the house roof. The Tuscan Classical Revival columns supporting the porch are a sign of its being built in the Edwardian era.

There are other possibilities for the inspiration of single-storey, hipped-roof house-types in Victoria, such as similar houses observed in French North America or the Ontario Classical Cottage of the 19th Century. Classical Cottages generally have a smaller, more formal entry porch. They often have features borrowed from the dominant style of larger houses at the time they were built: the Italianate cottage typically has eaves brackets and a front angled bay window balancing the entry porch, both with hooded roofs, while if it has turned “gingerbread” porch supports and prominent, asymmetrically placed, pedimented bay windows it would be called a Queen Anne Cottage.

Classical Revival

Modern western civilization has long recognized that its roots lie in the cultures of classical Greece and Rome, and there have been several architectural movements based in some part upon emulating buildings of ancient times. Sometimes this has been manifested as a direct copying of Greek or Roman buildings. Other styles have been based on designing buildings according to the same rational principles used by classical architects, such as symmetry, balance, and proportion.

In addition to the specific styles it produced, the classical movement also contributed eclectic elements to other different styles. This was particularly the case in the period from around 1900 to 1914, when many houses became simpler and more symmetric, and made use of ornamental dentils and columns. This is sometimes referred to as the Edwardian Classical Revival.

Neoclassical Style

The World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, widely publicized several impressive buildings based on classical themes, and inspired many similar architect-designed buildings in the United States and (to a lesser extent) in Canada over the next half-century. Only a few examples of these are seen in relatively pure form in Victoria, mostly in commercial or institutional buildings. Typically there is a domination of the façade (and sometimes the sides) of the building by a porch that appears to have been taken from a Greek temple. Although the bulk of the building may obviously be a different style, it is usually symmetrical and may have classical details.

Neoclassical

This building at 1600 Quadra (North Park), designed as the First Congregational Church in 1913, is a symmetric brick building fronted by two-storey Ionic columns supporting a wide frieze and a triangular pediment. Classical details are the modillions under the eaves and dentils on the cornice, and the three triangular pediments above the entrance doors.

Homestead Style (Vernacular)

Homestead Style – 2011 Cameron Street

The first North American interest in classical buildings occurred from around 1770 to 1860, after the American Revolution when the republican concept of Rome fired the public imagination in the United States and suggested an architectural model, first for public buildings and then for homes. Well-known examples are the Gone with the Wind columned mansions built in the southern states before the Civil War. This was too early to directly affect developments in Victoria. However, numerous simpler vernacular approximations to these houses were subsequently built throughout North America, particularly in rural areas, and remained popular long after the demise of the formal style. The type ultimately became a favourite for inexpensive working-class houses built on narrow city lots. They are typically 1½ or two storeys tall, with a front-gabled roof and a porch that can be recognized as approximating the form of a Greek temple. For this reason they are also called Temple Houses.

Homestead Style

It is doubtful that the builders of this 1892 house at 2011 Cameron (Fernwood) were thinking of a Greek temple when it was constructed, but its similarity to mid-19th-Century houses that were designed on classical models is clear. It is close to symmetric and has a modestly pitched front-gabled roof, in this case with an incomplete pediment and cornice returns. There is a board frieze under the eaves, while cornerboards represent pilasters. The porch even has three square supports approximating Corinthian columns with stylized fretwork foliage in the capitals.

Georgian Revival Style

Another architectural style based on principles of classicism was Georgian, which began as a favourite for British stately country homes. A few vernacular Georgian homes (for example, Craigflower Manor in View Royal) were built by pioneers in the Victoria area. However, the only surviving examples of the style within Victoria date from the beginning of the 20th Century, when it enjoyed a revival of interest that has continued to this day.

The original Georgian houses were designed by British architects influenced by the classical principles of balance, symmetry, and simplicity as they perceived them in Italian Renaissance buildings. The classic Georgian house is a simple, two-storey, rectangular box with a hipped or side-gabled roof, and door and windows symmetrically arranged on the front façade. It typically has five double-hung sash windows on the top floor, and a central door and four windows at the ground level. The front entrance is the focal point of the façade, drawing the eye by being the most elaborately decorated feature of the house, projecting forward in a gable, or being enclosed by a porch. There are often classical features such as columns, pediments, modillions, or dentils on the house.

Georgian Revival

This Georgian Revival home at 1509 Rockland (Rockland) was built in 1922. Like most Revival houses it deviates somewhat from the original Georgian style: it has one window too many on the top floor. Apart from that it has many of the relevant features, such as symmetry, classical pediments on the dormers, and a door enclosed by a pedimented porch with classical columns. Most Georgian Revival houses in Victoria deviate even further from the norm with features such bay windows, multiple windows, and off-centre doors, not found on original Georgian models.

Romantic or Picturesque

Around the beginning of the 19th Century there was a reaction to the principles of Classicism, intellectual assumptions such as the appeal of simple symmetric structures determined by geometric rules. Instead, a new movement called Romanticism proposed aesthetic standards based on how buildings arouse emotional reactions in the observer (a similar development in music occurred when composers such as Tchaikovsky and Wagner moved away from the music of Bach). Such houses are often called Picturesque because their appearance was considered appropriate to be the subject of a painting. The Romantic or Picturesque styles were inspired by the architecture of particular historical periods, although they were often not very accurate copies of buildings of those times.

Gothic Revival Style

Gothic Revival

The first Canadian buildings in the Gothic Revival style were churches built at the beginning of the 19th Century, when it became considered as appropriate for religious and public buildings because of its associations with medieval European Christianity. It had earlier been used in England for grand country houses, and from there became popular for residences in the United States and Eastern Canada from about 1840 to 1865. Originally a style designed for masonry buildings, it was adapted to frame construction in a form called Carpenter Gothic for simpler homes. In Victoria it is mainly seen in churches and in residences originally built in country settings in the 1860s, although a few later examples can be found. Typical Gothic features are steeply gabled roofs with cross gables, elaborate carved bargeboards, flattened arches in porches, and pointed-arch windows (or rectangular windows with frame mouldings giving that effect) often extending into the gables.

Wentworth Villa was built at 1156 Fort (Fernwood) around 1862 in Carpenter Gothic. It is typical of how the Gothic style was applied to a modest residence with its steep side-gabled roof, centred wall-gable in the front façade, and intricately carved bargeboards. The wraparound porch with its support brackets simulating a flattened arch, and the token ornately detailed pointed window set prominently in the peak of the wall-gable, are examples of how an otherwise simple house could be transformed into a recognizable style.

Italianate Style

Houses based on Italian models were very popular in Victoria from 1860 to the turn of the 20th Century. Many of the first residences constructed on extensive estates outside town were inspired by the informal villas of the Italian countryside and were given the label “Italian Villa” style. These were rambling, two-storey structures, their low-pitched, gabled roofs frequently having widely overhanging eaves with decorative brackets beneath. They had tall, narrow windows with arched tops or hoods above them. The earliest examples had a prominent front-facing gable; a few later ones had a tower, almost always in the angle of two wings of the main building (rather than at a corner, as in Queen Anne houses).

Fairfield at 601 Trutch (Fairfield) was built in 1861 on an estate that would later become the neighbourhood of that name. It is a frame building, with rectangular windows topped by hoods, unlike the segmentally arched ones typically seen on stone or brick houses.

A second Italian house style that proved attractive in early Victoria was the Cubical Italianate. This was a severe, two-storey, symmetrical, box-shaped building with a hipped roof and bracketed eaves. The originals were always stone, brick, or stucco, and usually had arched windows, belt courses, and corner quoins.

Italianate Style

Built in 1860 (and demolished in the 1960s) on a country estate that was later subdivided to become the neighbourhood of the same name, Fernwood was a good example of Cubical Italianate. It had a simple entry porch with square supports and a flattened arch.

Although the Italian Villa and Cubical Italianate forms were easily distinguishable in the 1860s, subsequent builders frequently built houses that were a composite of the two types that became known simply as “Italianate style.” Houses with several wings had hipped roofs, 1- or 2-storey bay windows were often added, and Classical Revival features such as triangular pediments on gables became common. At the end of the 19th Century many simple box-like structures were made stylish just by the addition of some eaves gables and window hoods. To complicate things further, many builders of Queen Anne houses added Italianate features, so that assigning a single style becomes debatable for many houses.

Second Empire (Mansard) Style

This style reached North American notice because of its part in the extensive building program undertaken during the reign of Napoleon III (1852-1870), France’s Second Empire. So although it had its origins in the French Renaissance, it was perceived at the time as being a modern and very up-to-date introduction, in contrast to the Romantic and historic nature of the revival styles. Perhaps for this reason it was short-lived – it was used in Victoria for four public buildings in the period 1875-1882 (the Customs House, City Hall, the Masonic Temple, and the now-demolished Central Boys School) and a handful of surviving residences built around 1890.

Second Empire

The distinguishing feature of Second Empire is its mansard (dual-pitched) hipped roof that changes from a steep to a shallow angle. The steep portion of the roof can be straight, or curved in complex ways, and typically will have dormer windows in it. The remainder of the house is usually very similar to an Italianate home. A classic example of a Second Empire house, Trebatha at 1124 Fort (Fernwood) was built in 1887. Its roof begins with a flare and then straightens, topped with a shallow hip. The rest of the building is indistinguishable from a Cubical Italianate house with its narrow double segmentally arched windows.

Queen Anne Style

This style is the epitome of a Picturesque building style. Supposedly inspired by the architecture current during the reign of Queen Anne (1702 – 14), the concept was in fact created by a group of British architects in the 1860s working from late medieval models, which also provided inspiration for the Gothic and Tudor Revival styles and the Arts & Crafts movement. The first Queen Anne built in Victoria beginning in the 1880s represented this British school. But the style was modified south of the border to a more flamboyant architectural expression (typically with a wraparound entry porch decorated with spindlework), and the 1890s saw several still surviving homes built in a more North American mode. In Victoria the style was also frequently modified with Italianate elements, and in its dying days in the first decade of the 20th Century (Edwardian Era) Classical Revival features were often added.

This style was the antithesis of the simple, symmetric Classical approach. Victoria’s typical Queen Anne house has a steep hipped roof and two or more gables projecting irregularly, although a few are front-gabled. More elaborate dwellings will have a tower, usually octagonal or round, projecting from a front corner. The defining characteristic, however, of the style is its variety of surface treatments – a Queen Anne house will use almost anything to avoid a smooth-walled appearance: pent roofs, cutaway bay windows, projecting gables, half-timbering, patterned shingles, terracotta tiles in brickwork.

Roslyn (1135 Catherine, Vic West: drawing from photo courtesy CVA PR252-7098) also dates from 1890, but illustrates how the style had developed after being imported to the United States; this house was built from a mail-order plan by American architect G.F. Barber. On the porches it shows the feature most popularly associated with the Queen Anne style, spindlework. It also demonstrates many of the elements used to avoid flat wall surfaces: projecting gables, pent roofs, horizontal siding, and a variety of shingle patterns.

This is a picture of 223 Robert (Vic West), built in 1903-04. It has many typical features of the late Victorian Queen Anne style such as the fancy shingles and pent roof in the gables, the cutaway bay windows, and the Italianate brackets under the eaves. However, the beginning of the transition to the Edwardian period is marked by touches such as the discreet narrow beveled siding and Classical Revival features like the Tuscan columns on the porch. Smaller single- or 1½-storey versions are called Queen Anne cottages.

This style originated on the northeastern coast of the USA, principally in vacation residences in fashionable resorts, and inspired several Victoria homes and churches at the end of the 19th Century. The defining feature of a Shingle building is wall cladding of continuous wooden shingles, almost like a skin, which unifies the irregular shape of the house within a smooth surface. They often have substantial masonry foundations or ground floors. Their roofs are typically steep and may be gabled or hipped with cross-gables (like the Queen Anne), and like that style they are usually rambling, asymmetric buildings. They also frequently have corner towers, usually integrated bulgelike into the body of the house, rather than attached as distinct structures. The classic examples of the style emphasize the horizontal lines of the building, strips of multiple windows often contributing to this impression. Shingle buildings often also incorporate Romanesque arches and Classical Revival details such as Palladian windows.

This house built in 1896 at 1032 McGregor (Rockland) is based on what appears to be a rubble stone foundation, above which it rises like an irregular pile of simple geometric forms, all bound together by a shingled casing. Window surrounds have little decorative detail, and the continuity of the surface has minimal interruption from features such as corner boards and stringcourses. A multiple string of windows runs around the top of the tower and across the overhanging gable in an attempt to counteract the vertical impression given by the building’s sitting on the brow of a hill.

Arts & Crafts

This was not as much a style as an ideological movement, although the Victoria architects who were influenced by it left a recognizable mark upon the local landscape. The Arts & Crafts movement is most simply summarized as one initiated by a group of British artists and architects reacting to several features of Late Victorian life, principally the dehumanizing effects of industrialization and the unquestioning imitation of earlier formal historical styles. Rather, they espoused architecture that showed evidence of human handiwork, that was functional, and that respected British vernacular traditions of house building. Ironically, their admiration of the vernacular meant that they often incorporated elements from medieval buildings in their work that were also copied by the proponents of the Gothic, Queen Anne, and Tudor Revival styles that they criticized. As a result, it is sometimes difficult to discern the boundaries between these different styles.

Tudor Revival

Tudor Revival (also known as English or Elizabethan Revival) is a style that was created to evoke the spirit of traditional medieval English structures, particularly rambling country manor houses and rural cottages. The first examples were architect-designed stately homes in late-nineteenth century England that mimicked the appearance of growth through centuries of additions. Throughout the British Empire, and in Victoria in particular, this architectural style came to symbolize a traditional British way of life. There are a few instances in Victoria of homes similar to the original, historically inspired prototypes. However, most examples of the style here use it in eclectic mixtures. Many local architects (notably Samuel Maclure) used selected Tudor Revival elements in their designs, apparently to appeal to their clients’ Anglophile bents, but without attempting to create historically accurate copies. And a large number of more modest homes built in the first third of the twentieth century were modelled on medieval cottages in a subset of the style called English or Cotswold Cottage, which sometimes included an attempt to simulate a thatched roof.

Tudor Revival

The style is described here as a set of features frequently found in houses that are at least part Tudor Revival. The more features that appear in a given building, the closer it is to the style. Hatley Park, designed by Samuel Maclure, with Douglas James, and illustrated here, is possibly the purest version of Tudor Revival to be found in the Capital Region.

- steep, side-gabled roof

- one or more steeply pitched front gables, often asymmetric or overlapping

- decorative half-timbering inset with masonry (usually stucco) (This may also be found in the gables of Queen Anne and Arts & Crafts houses, which derive from medieval models as well. Half-timbered gables and walls usually indicate a Tudor Revival house.)

- entry with either no or a small porch, frequently with a flattened, pointed (Tudor) arch and quoin-like tabs of brick or stone projecting into the surrounding masonry

- oriel windows

- either rows of three or more casement windows, or tall narrow windows, often with multiple panes or leaded diamond glass

- jettied upper storeys (also indicative of Queen Anne and Arts & Crafts houses)

- massive chimneys on an outside wall, sometimes with multiple flues (This can be a feature distinguishing Tudor Revival from Queen Anne and other types of Arts & Crafts houses, whose chimneys are usually internal.)

- crenellated towers and bay windows

British Arts & Crafts

The British Arts & Crafts concept was attractive in Victoria to “Little England” enthusiasts intent on recreating the homeland on Canadian soil. A large number of architects with appropriate backgrounds were available to oblige by providing house designs in this genre for upmarket clients. As the British models they worked from were diverse, so were the Victoria houses they produced; as well, individual architects added their own idiosyncratic touches to their work. But there is a common mood to these houses: although they look like they have just been plucked, steep-roofed and asymmetrical, from the English countryside, they don’t look out of place in a British Columbian suburb, particularly in terms of their building materials.

Brothers Douglas and Percy Leonard James, both trained in England, designed 1015 Moss (Rockland; drawing from photo, 1977, Hallmark Society), built in 1912-13. It is clad largely in shingle, but features many medieval British features such as half-timbered panels, leaded-glass windows, and oriel window on the side. The prominent gable on the left of the façade, with its recessed arch and two-storey bay window, looks as though it has come from an earlier Queen Anne, but there is no variety-for-variety’s sake in this house: it has an overall unity to it.

Edwardian Vernacular Arts & Crafts

This vernacular house type with strong Arts & Crafts features, although not unique to Victoria, seems to have been built here in larger numbers than anywhere else. Thousands were constructed during an economic boom between 1904-1914; fewer can be traced to before or after that period. Most were built by contractors such as David Herbert Bale, and do not seem to have been architect-designed, although it has been suggested that some of the houses of renowned Victoria architect Samuel Maclure provided a model for them.

The basic characteristics of this house are a height of 1½ storeys, with the second level designed for living space, and a front-gabled roof pitched at approximately 45 degrees, with the gable ends at the top of the main floor walls. There are typically one or two dormers, usually gabled. Half-timbering and dentil mouldings are often seen in the gables, and many have wide bargeboards with eave returns at the bottom. Earlier instances typically have closed eaves; later ones may have open eaves and exposed rafter tails similar to those in Craftsman houses. Almost all have an asymmetrical main floor on the front facade, with inset entry porch on one side of the façade and a bay window on the other, and a symmetrical upper level.

The façade of 1127 Fort (Fairfield) built in 1907, is suggestive of a gable on a Queen Anne house (which is related to the Arts & Crafts movement) in its multiple levels and surface treatments. The half-timbered gable and prominent roofline are reminiscent of several high-fashion Arts & Crafts houses based on a Swiss Chalet model designed a few years earlier by Samuel Maclure.

Craftsman Style

The Arts & Crafts philosophy was taken up in the United States by furniture maker Gustav Stickley in his magazine The Craftsman, where he made available plans for houses in that fashion for free; the magazine name subsequently became identified with the American version of the style. Stickley stressed the use of low, broad proportions, natural building materials, and the absence of artificial ornamentation in his houses. Two California architects, brothers Charles and Henry Greene, popularized Craftsman-style bungalows, and shortly after 1905 the style and house type became the dominant one for smaller American houses until the early 1920s; in fact, the style is frequently referred to simply as “Bungalow.” Many companies sprang up to offer building plans, full kits of building materials that could be shipped to the customer’s lot, or complete design and construction services to erect a house in this style. Many Victoria Craftsman bungalows, two-storey houses, and even a few Craftsman churches date from this period.

Craftsman buildings tend to differ from British Arts & Crafts structures in having lower-pitched roofs. Their ornamentation, although its medieval origins are discernable, is more stylized; almost all Craftsmans have open eaves with exposed rafter tails, many have decorative beams or triangular braces under their gables, and local examples frequently have some token patches of half-timbering. They are usually side- or front-gabled, and have a front entry porch: in simple examples this will be incorporated under the main building roof, while more elaborate structures will have a gabled or shed-roofed porch in front. The porches on many Craftsmans have square supports based on battered stone piers or shingled balustrades. Bargeboards on gables are usually wide and frequently are slotted and have pointed tips.

Craftsman Style

This house was built in 1911 at 20-24 Douglas (drawing from photo c.1913 from Craftsman Bungalow catalogue, courtesy Larry Kreisman) from Plan 327 designed by architect Jud Yoho of Seattle. Massive stone pillars support the porch; more commonly in Craftsman houses the stone would extend only part way up as a pier, and wooden supports would rest on them. The open eaves, exposed raftertails, and beam-ends with brackets under the gables are typical.

Foursquare (Vernacular)

A group of Chicago architects, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and known collectively as the Prairie School, originated a uniquely American house style at the beginning of the 20th Century. Many of these houses had low-pitched, hipped roofs with widely overhanging eaves, emphasizing horizontal lines. While this movement seems to have had minimal impact on professional architecture in Victoria, from houses scattered throughout the city there is ample evidence that builders, following their gut feelings on what clients wanted, were constructing scores of residences influenced by the style, presumably from the many pattern books available. Most date from shortly before WWI.

This house type is known as a Foursquare or Prairie Box. The basis of its appeal was in part functional – it is essentially a two-storey version of the Colonial Bungalow that had been an evergreen favourite for decades earlier because it was cheap to build. The introduction of platform frame construction would have decreased the cost of adding a second storey. In form it is also an expanded version of the Cubical Italianate that had been fashionable a generation earlier, minus the bay windows and eaves brackets, and plus some dormer windows on an expanded third level.

The classic Foursquare (so-called because it typically has four rooms on each level) is a hipped-roof cube with features that emphasize its horizontal lines: wide watertables, belt courses, and friezes separating levels of the building; contrasting materials at different levels; wide front porches; and multiple strings of windows. It usually has at least one dormer window.

Foursquare

This Foursquare at 123 Howe (Fairfield, not on City’s Heritage Registry) is a classic of the type. Its horizontality is accentuated by three bands of smooth boards girdling the house and separating the sections of rougher cladding, alternating claddings of shingle and bevelled siding, and contrasting colours for the different materials. All windows in the façade are in groups of three, there is a wide, low front porch, and the low front dormer further stresses the flattening effect of the bellcast roof.

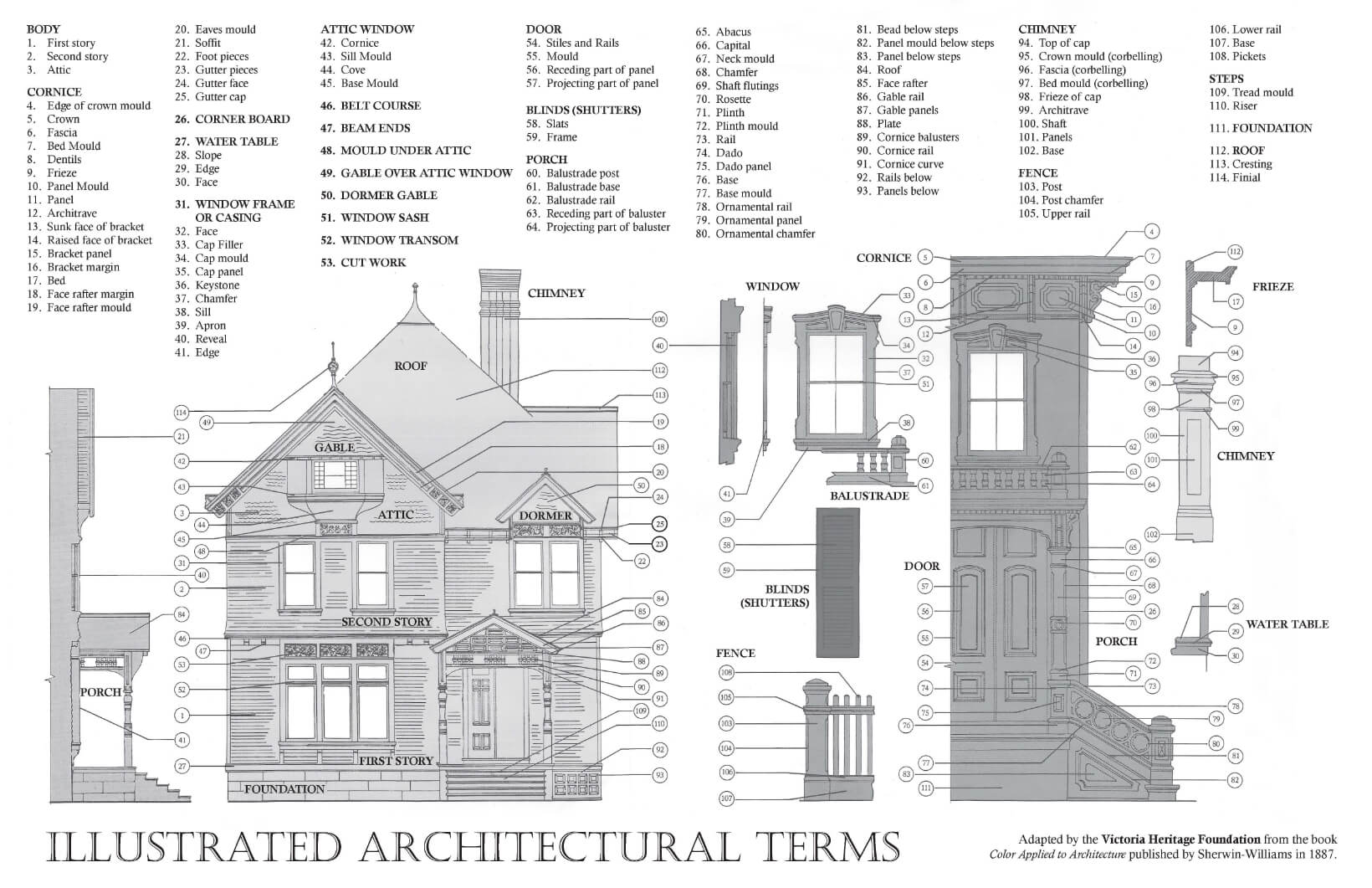

Glossary

Discover the architectural terminology you can use during your next tour of heritage homes. This glossary will deepen your understanding of the various design elements that make each property special. If you’re not already familiar with the language of housing design, this glossary makes a handy reference. By expanding your vocabulary and knowledge base, you can clearly articulate what you love about each home you see.

Alphabetically Ordered Terms

Architrave – beam that spans from column to column.

dentilated (denticulated) – ornamented or embellished with dentils, as in a cornice or gable moulding.

dormer – structure containing windows, which projects from roof slope, and has a flat, sloping (shed), gabled, hipped or other shape of roof.

unevenly-coursed shingles – two rows of shingles laid close together, creating a rhythmic pattern, more frequently used on walls than roofs.

double-bevelled siding – exterior wall cladding consisting of a single drop siding board, usually ship-lapped, milled to present the shadow lines of two boards. Commonly used by 1910. Also referred to as double-wave or double ogee siding.

double-glazed – window with two panes of glass set apart in the same sash.

double-hung sash windows – window with two sashes hung in same frame; by use of

weight-and-pulley system, one sash goes up and the other, down.

dowel, dowelling – pin of metal or wood used to secure two members together.

drop finial (pendant) – ornamental feature placed inside apex of roof, below wall overhang, etc.

drop siding – horizontal exterior wall cladding, usually shiplapped, but sometimes with tongue and groove versions. Also referred to as channel siding.

duckboard – platform of slats or duckboards laid on cold or wet surface to form a pathway.

duroid – type of asphalt shingle.

eave – lower edge of roof.

elevation – face or facade of building, or drawing of face.

entablature – band of horizontal elements above column capitals, composed of architrave, frieze, and cornice.

entasis – slight convex curve on columns and other structures used to create optical illusion and make sides appear straight; sometimes exaggerated for decorative effect.

façade – face or side of building; most often used when describing the front of a building.

fanlight – window in arched opening over door.

fascia – horizontal board which covers rafter ends along eaves of roof.

fenestration – window arrangement on building facade.

finial – ornamental feature placed at apex of gable, hip, etc., or (rarely) where bottom of gable meets eaves.

floor plan – scale drawing of arrangement of rooms, etc., of one level of a building.

frieze – decorative horizontal band at top of exterior and interior walls below cornice, or as porch cornices.

gable roof – peak formed with single slope on either side of ridge.

gambrel roof – roof with pair of shallow pitched slopes above steeply pitched slopes either side of ridge.

half-hipped gable – gable with top truncated or clipped back to ridge; also called jerkinhead gable.

hip – angle formed by intersection of two sloping roof surfaces.

hipped roof – roof with surfaces sloping in four directions; can be pyramidal, ridged or flat-topped.

hood moulding – projection from a wall above a doorway or window to keep rain away from opening.

horn – projecting upper or lower ends on side bars of moveable window sash which prevent sash from hitting upper rail or sill of window frame.

jettied (jettyed) – projection of an upper storey or other member of a structure over the part below.

keep – chief tower of a castle.

keystone – highest and central stone, frequently wedge-shaped, of an arch.

lancet window – long, narrow window topped by pointed arch.

larder – small room where food is kept (pantry).

lintel – horizontal member laid across top of doorway or window opening to support wall above.

modillion – horizontal ornamental block or bracket under eaves.

mortar – mixture of lime, plaster or cement, fine sand and water, used for bonding and pointing brick or stone.

moulding (molding) – decorative finishing strip.

mullion – vertical bar of wood, metal or stone which divides a window into two or more parts.

muntin (also munton bar, sash bar) – thin strip of wood holding panes of glass in window.

newel (newel post) – principal supporting post for handrail at bottom or angle of staircase.

oriel – small curved or angled window section, projecting outward from wall and supported by brackets.

Palladian window – window consisting of central arched sash flanked by smaller side lights, not arched; aka: Venetian or Diocletian window.

pantry – small room where food, dishes, etc., are kept.

parapet – low wall around roof or platform.

parged, parging – covering of exterior element, such as a chimney, with mortar or form of stucco.

pebbledash, pebble-dash – external plaster or stucco normally consisting of two coats in

which pebbles or gravel are thrown into second coat before it has set.

pediment – low-pitched triangular end or gable above portico, door or window.

pendant – hanging ornament.

pent roof – visor-like roof that projects from wall.

pergola – open grid, supported by rows of columns or other upright members, for growing vines, etc.

piano window – small horizontal window high in the wall of main level, under which upright piano can be placed on interior wall; generally in living or dining rooms.

picket fence – fence with vertical pointed flat, square or round members.

pièce-sur-pièce – French Canadian type of log construction favoured by the Hudson’s Bay Company: a dressed timber frame structure with horizontal log infill, the logs notched at both ends and slid down the uprights.

pier – vertical supporting member, frequently battered and beneath posts or columns, as on porch or verandah.

pilaster – flat column against face of wall; usually projects no more than one-third to one-half its width.

pitched roof – roof with sloping sides.

pointing – finishing of rough mortar joints in masonry with special fine, strong mortar, shaped with special tools, usually coloured to contrast with brick or masonry.

porch – small, projecting, covered entrance to building; may be open, screened, or glass-enclosed.

porte-cochère – covered area over driveway at building entrance.

quarter-round – small moulding or beading which is one-quarter of circle in section, often used at junction of floor and baseboard.

quatrefoil – leaf-like motif with four lobes or circular areas; frequently the form of decorative windows.

Queen Anne sash or window – large glass pane edged with many small panes of square or rectangular glass, frequently coloured.

quoins – large stones or bricks which accentuate corners of a building; laid vertically, frequently alternating short and long blocks.

rake – slope of gable, pediment, staircase, floor (frequently in theatres).

raking moulding – moulding that follows slope of gable.

return (cornice return) – continuation of moulding, where bottom of raking moulding on a gable is carried a short distance back and horizontally towards centre of gable.

riser – vertical portion of stair step; can be open riser.

roughcast – exterior plaster or stucco with rough aggregate (gravel, broken bottle glass, etc.) thrown in, such as pebbledash.

sash – window frame which slides open vertically.

scullery – small room off kitchen where dishes, cutlery, etc., are washed or cleaned.

section – drawing illustrating view if structure were cut vertically, and interior exposed.

segmental arch – arch in which the curve is a segment of a circle but less than a semicircle.

shake – large, split wooden (generally cedar) tile used as wall or roof cladding; thicker and more rustic than shingle, and not tapered.

sheathing – material used to enclose and strengthen walls.

shed roof – roof consisting of a single slope.

shingle – sawn, tapered wooden (generally cedar) or asphalt tile used for exterior wall or roof cladding.

shiplap – grooved, interlocking boards laid diagonally over timber structure, as base for external wall cladding.

sidelight – narrow windows on one or both sides of entry door.

sill – structural framing member on bottom of door or window.

soffit – enclosed underside of overhanging eave.

spindle – decoratively turned or circular member in balustrade, porch frieze or gable decoration, etc.

spire – pointed top part of tower or steeple.

steeple – high tower of church.

storm window – supplementary window, put within same frame either outside or inside, to prevent loss of heat in winter and as sound barrier; if placed outside, it also protects main sash from effects of weathering.

stringcourse, string course – horizontal division of a building marked by band of wood, brick, metal or stone running across face of building (belt course).

tar paper – heavy building paper coated with tar to make it waterproof, used on walls and roofs, generally between layers.

terracotta – fired ceramic tile used as decorative architectural element.

transom window – small window or series of panes above door or window.

tread – horizontal portion of individual stair step.

trellis – lath lattice used as screen.

tongue-and-groove (T&G) – boards which join together by rib (tongue) on long edge of one board locking into groove on long edge of next board.

tripartite – composed of or divided into three parts.

trefoil – leaf-like motif with three lobes or circular areas.

truncated – top or end cut off, shortened or abbreviated.

Tudor arch – late-medieval style of flattened arch with vertical sides, rounded shoulders and a point.

turret – small slender tower, frequently at building corner.

tuscan column – simplest order of Classical styles, unfluted with plain round capital and base.

tympanum – triangular space enclosed within pediment.

V-joint – tongue-and-groove boards with chamfered edges on top side of boards.

verandah – large roofed space (sometimes a big porch) attached to exterior wall of house, with roof supported by columns, posts or piers.

vernacular – structure built or designed by someone without formal training, structure not conforming to established styles except possibly in some ornamental details.

wainscoting (wainscotting) – panelling, usually wooden, on lower portion (wainscot) of interior walls.

wall dormer – dormer flush with face of wall, or rising up from wall, breaking through eaves and roof plane.

water-table, water table – horizontal wooden or metal strip set at angle between exterior wall cladding, between main and lower levels, to divert water away from foundation.

whitewash – water-soluble white liquid, usually of lime and water, which was used as paint on walls and fences.

widow’s walk – flat top of roof and its surrounding cresting or parapet.

Heritage Houses & Insurance

There have been recurring questions regarding the escalating costs and availability of property insurance for heritage houses. In addition, it has become evident that in relation to Heritage-Designated properties, some clarification may be helpful.

What Does Heritage Designation Mean?

There are over 600 houses that are listed on the City of Victoria Register of Heritage Properties. Approximately 400 are Heritage-Designated and 200 are Heritage-Registered.

A Heritage-Registered property does not have legal protection and Council approval is not required for maintenance or alterations to a Heritage-Registered property that is not located within a Development Permit Area or Heritage Conservation Area.

A Heritage-Designated property is protected through a municipal heritage designation bylaw and may not be altered or demolished without Council approval.

A heritage property is not designated because of its age, but rather, by its heritage value.

The intent of designation is to preserve the historic, physical, contextual or other community heritage value of a property.

Most designations cover only the exterior of the building, not the interior. For properties whose interiors are not designated, the owner is free to alter the interior, provided that it does not impact the exterior of the building and it satisfies applicable building codes.

Owners of Heritage-Designated properties should consult the Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada (Government of Canada, 2010) to determine what changes are acceptable and the appropriate design approach in order to ensure the conservation of heritage values.

If a designated building is completely or substantially destroyed, it is most likely that the heritage values associated with the property would also be destroyed. When heritage values no longer exist, the corresponding designation bylaw that designated the property would have no relevance. In addition, a designation bylaw does not oblige the owner to replicate any lost heritage attributes. A replacement building, for example, can be of a different design.

Will Heritage Designation Affect My Home Insurance?

In recent years home insurance rates have escalated across the board affecting all properties within certain areas.

Due to recent natural disasters around the world, home insurance companies have reassessed risks, tightened their underwriting criteria, and some insurers are reluctant to take on risks that may not have been a concern in the past.

Insurers are looking for ways to minimize their risks.

Given the above clarifications as to what heritage designation means, designation itself should not place additional requirements on the insurer and therefore should not affect premiums.

A variety of other reasons may cause insurance companies to increase premiums for older buildings if there is a higher level of risk, such as out-dated wiring, old heating systems, etc. These risks are not unique to heritage houses. Many hazards (aluminum wiring, certain types of plastic water pipe, asbestos, vermiculite insulation) are often found in newer houses.

Since there are no insurance industry standards, each insurance company can develop their own policy requirements.

Some insurance companies may not insure heritage houses or those over a certain age.

Several companies will insure older houses. Some may carry out site inspections to identify specific perceived risks which can then be addressed.

As with any insurance plan, it’s best to research the various insurance providers in order to find the most competitive rate and best service from your insurer.