Building Community

Whether you’re interested in learning more about Victoria’s heritage homes or you own one yourself, VHF has the resources to answer your questions.

About James Bay

The fertile flat land of Beckley Farm across the Bay from Fort Victoria is the neighbourhood we now know as James Bay. The farm provided food for Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) personnel at the Fort, established in 1843 by Sir James Douglas; Queen Victoria later appointed him Governor of Vancouver Island, then British Columbia (BC). James Bay and Douglas Street were named for him.

After construction of the first government buildings for the Colony of Vancouver Island in 1858, James Bay became desirable residential property for Victoria’s social and political elite. During the 1880s and ’90s, James Bay’s west end became an important industrial area. This led to further residential construction, for workers’ houses and “widows’ cottages,” rental houses for annuity income. Grand homes, like 228 Douglas St, continued to be built until the First World War. Redevelopment and modernization in the 1950s-70s destroyed many historic structures.

However, continued activism by this close-knit community, and a change in attitude and policy by municipal government, helped to stem the tide of highrises, and to preserve a large number of James Bay’s heritage buildings. But the current building boom is once again taking its toll on more of James Bay’s beautiful old homes and streetscapes.

Fairfield

Fairfield was still largely undeveloped until the arrival of the electric street car line. This coincided with Victoria’s largest building boom that began in 1907 and ended in 1913. Swamps were drained and the streams culverted. The dairy farms, Chinese market gardens and the skating ponds disappeared. Early municipal planning decisions were designed to create a utopian suburban vision for Fairfield. Boulevarded streets with residential lots were laid out in a rectilinear grid. The No. 6 Foul Bay streetcar line began operating in 1909 and intensive development took place along the route soon after. The land boom resulted in a very competitive building industry with many spec-built houses. Houses were often built and financed on the installment plan by local builders such as W. Oliphant, J. Moggey and A. McCrimmon as well as the larger construction companies of The Ward Investment Co. and The Bungalow Construction Co. They often purchased several lots in a row and built similar looking homes. This rapid development of Fairfield resulted in a cohesive and successful, middle-class neighbourhood of mostly single-family homes with small private gardens.

Fairfield has remained a dynamic community that is a reflection of its residents and their times. The WWII war-time demand for cheaper accommodation and the difficulties of sustaining large houses in the post-war period resulted in many homes being converted into suites. A similar trend is seen today, with homeowners and developers renovating and sometimes raising houses to create additonal suites. It is hoped that this is done in a sympathetic way that preserves the architectural style of the buildings and the human scale of the streetscape.

Fernwood

By 1849, the entire townsite region was deeded to the Hudson’s Bay Co which surveyed it and sold large portions to early colonists. Surveyor Benjamin Pearse acquired a hilly heavily wooded parcel in ‘the country’ beyond Spring Ridge. On a hill above present day Begbie St, he built a fieldstone mansion he called Fernwood Manor in keeping with the landscape. This home, which stood from 1860 to 1969, is the source of the neighbourhood’s more contemporary name. Originally a wilderness area of Garry Oak meadows alive with wild flowers, springs, swamps and small lakes, Fernwood also contained sand pits and gravel banks which supplied materials to build the growing town.

When Victoria started piping water from Elk Lake in 1875, the area of the springs became municipal gravel yards used to pave roads and sidewalks and as fill in James Bay for the building of the Causeway and the Empress Hotel in the early 1900s.

The California gold rush of 1858 spurred the expansion of Victoria and by the 1880s more lots had been subdivided in the Fernwood district. These were initially developed with cabins and cottages. The introduction of a street car line in 1890 led to rapid residential development of comfortable homes for the swelling middle-class population.

North Park

The northern portion of North Park was developed much later than the southern, because it was originally part of Roderick and Sarah Finlayson’s farm estate. Finlayson, a Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) Factor, was in charge of Fort Victoria from 1844 to 1849. He purchased 103 acres from the HBC in the 1850s, and built Rock Bay in the block now surrounded by Douglas, Bay, Government and Queens. Finlayson died in 1892, Sarah in January 1906, and the estate was subdivided. About that time, the rock was blasted for Bay Street between Wark and Quadra.

Many homes were built in North Park from 1907 to the beginning of World War I (WWI), a period coinciding with Victoria’s greatest building boom, although the market had begun to collapse by 1913. The neighbourhood was close to downtown and City Hall. Several new schools were built near by, and NP can still boast of churches of many denominations. A number of the City’s recreational venues are found here, including Royal Athletic Park, the Memorial Arena, the Curling Club & the Crystal Pool. Central Park, the city’s second oldest park, is well-used for ballgames and other events.

This newly-developing area of North Park was one of the first suburban neighbourhoods to which wealthy Chinese businessmen and their families moved before WWI. Possibly the finest house in the area, Lim Bang’s, is now gone. By World War II, there were many Chinese families here, such as the Lees and Tongs on Empress, the Chus, Lowes and Wongs on Queens, the Lou-Poys, Lowes and Wongs on Pembroke, the Chans and Quans on Cook, and the Joes on Vancouver. Their children went to George Jay School for regular schooling, and the Chinese School on Fisgard Street after hours.

Hillside-Quadra - Smith Hill

Hillside-Quadra is within Section IV of Joseph Pembertons’s original 1851 survey of Victoria. It was purchased by the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Chief Factor John Work (Wark) in 1852 who named it Hillside Farm. Many of the area’s streets are named after John and Josette Work’s 12 children. Until the end of the 19th century the area was largely agricultural and sparsely populated with market gardens and pastures remaining near Topaz and Quadra for some time. The first subdivision of Hillside Farm began in 1885 west of Quadra and was known as Hillside Extension. The dominant building in the area was the 3-storey brick Hillside Jail near the site of the current S.J. Willis School. The Victoria & Sidney Railway operated along Blanshard Street from 1894 to 1919. Most of the houses in Hillside Extension, along with North Ward School, were demolished in 1961 as part of an urban renewal project which included redeveloping Blanshard Street as the main access route between downtown and the new Swartz Bay ferry terminal.

The land east of Quadra and north of Hillside was subdivided as Hillside Extension C in the late 1880s. Smith Hill is named after William J. Smith, partner in the building contractors Smith & Elford. They also operated Victoria Brick & Tile Co., one of several brickyards at the present-day site of Mayfair Mall. Smith built a substantial brick house and stables on Montrose Avenue in 1892. The house later became Sunhill (tuberculosis) Sanatorium, taking advantage of the fresh air away from the City.

Most of Smith Hill was developed during Victoria’s largest building boom from 1907 to 1913. Some houses were built as rental income properties while the upper slopes of Smith Hill, with their fine views, developed into a fashionable middle-class neighbourhood. WWI and the economic depression brought a halt to most residential construction. WWII, the post-war demand for affordable accommodation and the economic difficulties of maintaining larger houses resulted in many homes being converted into suites.

Quadra Village, the 2-block commercial area at Quadra & Hillside, is the centre of this diverse community. The Village has recently undertaken several revitalization initiatives. It is home to unique shops and restaurants as well as a period movie theatre.

Burnside Gorge

Burnside Gorge is a residential area located in the north-west portion of the City of Victoria.

In the late 19th century properties along the Gorge waterway were fashionable. In 1894 architect W. Ridgway-Wilson designed a Queen Anne style residence for industrialist Charles Spratt. Premier Richard McBride acquired it in 1908 and called it “Glenelg.” Unfortunately only one residence from this period –“The Dingle” (1885) – still stands. However Edwardian-era houses are still prevalent. Many were built after the Lohbrunner Estate was subdivided in 1908. New streets – Irma, Balfour, Albany, and Carroll – were laid out at this time. Wesley Mitchell, an entrepreneur from Manitoba, developed several nearby properties. In 1910 he was advertising “choice lots on Washington Avenue, close to the Gorge Road” for $700. Half-acre lots, “all cleared and fenced,” sold for $1,500. Some of these large residential lots still remain on Washington Avenue.

Residential development was facilitated by new infrastructure. In 1912, Gorge Rd East was paved and a new bridge over Cecelia Ravine was built. A new streetcar line, route № 10, opened that year: It traversed Burnside Rd East to Carroll Street. In 1912-13, an elementary school was built on Cecelia Rd. A striking number of “motorneers” [street car operators] lived in this neighbourhood. It also attracted middle-class school teachers, store managers, and professionals.

In 1916 the Canadian Northern Railway (an antecedent of the CNR) completed its line through the ravine, which is now parkland and part of the Galloping Goose Regional Trail. It crossed the trestle bridge over the Selkirk Water to rail yards in Victoria West. In the other direction, the railway went to Patricia Bay. Until the 1920s, there was a passenger service to Pat Bay.

Despite the Depression in the 1930s, several new homes were built. Residential construction accelerated towards the end of the 2nd World War. In the 1950s, motels sprouted along the Gorge Road, which extended past Harriet Rd. and connected to the “old” Island Highway at Craigflower Bridge. This was the main route to the Western Communities and the Malahat until the Trans-Canada Highway was completed in the late 1960s. Most of the motels have now been converted into apartments or social housing. But visitors can still find accommodation at a few places, including a motel (279 Gorge Rd. E) that occupies the site of Sir Richard McBride’s residence, “Glenelg.”

Vic West

Vic West is part of the traditional territory of the Songhees First Nation, or Lekwungen, Coast Salish people. When the Hudson’s Bay Co. established Fort Victoria in 1843, the Songhees moved their village across the harbour from the fort, where they lived in plank longhouses and played an important role in the local economy. In 1911 the Songhees were relocated to their present location in View Royal and the site was used for industrial development.

Vic West has long been valued for its direct access to the Inner Harbour and the Gorge Waterway, its views to the Olympic Mountains and meandering shoreline dotted with pocket beaches. These attributes made it a favourite spot for the prominent families of the 1880s and 90s to build their homes. The largest and grandest of the homes built along the shore of the Gorge was Burleith. Built in 1892 by James Dunsmuir, son of wealthy coal mine owner Robert Dunsmuir, it was destroyed by fire in 1931.

The wealthy of Vic West lived alongside the working class. Much of the residential and early commercial development occurred between the 1890s and 1913, facilitated by the arrival of streetcar service. Workers were employed by the nearby industries, including the Esquimalt & Nanaimo and BC Electric railways, shipbuilders, lumber mills, breweries, machine shops and foundries.

There was another brief flurry of building activity when the Burleith estate was subdivided in the 1930s. Growth after World War II was slow and many of the old houses fell into disrepair or were unsympathetically modernized.

The 1970s saw the beginning of the revitalization of the Vic West neighbourhood. As industries left the area, multi-family residential developments were built, resulting in a population influx and a building and restoration boom that continues to revitalize the neighbourhood.

Oaklands

The majority of development in Oaklands occurred between WWI and WWII. Before this, vast sections west of Bowker Creek and Hillside Mall were farmland. There were areas of swampland along Haultain Street. Although the area was surveyed as residential lots in the 1880s, the first significant building boom wasn’t until 1909-13. In 1908 an investment company proposed building houses on 350 lots covering 80 acres either side of Cedar Hill Rd, between Hillside and Bay. The development was to be known as Rockland Park. In 1911, suburban lots were advertised in the Daily Colonist newspaper for $500, promising “level lots, no rock”. Many lots were bought by investors and houses were built speculatively during the building boom. The development catered to moderate-income earners, and was promoted as “being only a mile from city hall, yet it possesses all the advantages with regard to pure air of rural surroundings”. The new residents were accommodated by an extension of the streetcar line along Hillside Avenue. The pre-WWI population increase resulted in the construction of Oaklands School in 1913. The boom ended in 1913-14, and the neighbourhood took many years to infill with more homes.

Hillside Mall, built 1962, and nearby Hillside Rd is Oakland’s main commercial centre. There is a charming cluster of small shops at Haultain Corners. In 1998 the original Oaklands Elementary School underwent a major renovation and continues in its role providing education to young children and serving as a resource to local community groups. The Cridge Centre’s (originally the BC Protestant Orphanage) landmark 1893 building at Cook and Hillside, is home to BC’s oldest registered non-profit society and continues to serve the community. Oaklands remains largely a neighbourhood of single-family houses and is popular with families. In recent years, residents have advocated and worked for the protection of natural areas and the rural ambience of the streetscapes.

Gonzales

The Gonzales neighbourhood is named for Spanish explorer Gonzalo Lopez de Haro, first mate of the Spanish ship Princesa Real, who helped chart the waters around Vancouver Island in 1790. In 1885 Joseph Despard Pemberton, the first colonial land surveyor, named his large farm and home Gonzales.

The introduction of the electric streetcar line along Oak Bay Avenue in 1891 was instrumental in encouraging early subdivisions. However, it was not until after the turn of the century that the improved infrastructure and 1907-1913 real estate boom, turned this area into a popular residential neighbourhood. Many houses were built and financed on the installment plan by local builders and developers who often purchased several lots in a row. The residential building boom ended in 1913-14, and the neighbourhood took many more years to infill with more modest homes.

The 2nd World War demand for inexpensive accommodation and the difficulties in sustaining large houses in the post-war period resulted in many homes being converted into suites. Following the 2nd World War, another housing boom saw the remaining vacant land developed.

Well-known Victorians are remembered in local street names. Charles E. Redfern was a jeweller and watchmaker who served as mayor. Dr. John Chapman Davie was a medical doctor and a Member of Parliament. Amphion St is named for HMS Amphion. Somenos, Quamichan and Cowichan Streets honour some of Vancouver Island’s First Nations.

Today, Gonzales is a desirable neighbourhood characterized by its tree-lined residential streets, historic homes, and landscaped gardens. While it appears to be mainly a single family neighbourhood in character, there are many secondary suites, strata and heritage conversions.

The Gonzales neighbourhood has evolved from Garry Oak meadows and farmland to one of Victoria’s most popular neighbourhoods in less than 150 years.

GIS Map

Explore VHF’s award-winning Heritage Neighbourhoods GIS (Geographic Information System) map. Click “View Larger Map” above for a larger version with more layers and functions. In this map you can activate additional layers from the “Contents” tab, including “Aerial Photo” which will allow you to zoom in to the rooftops.

Move around the map, zoom in and out, and click on the icons to learn more about the properties on the City of Victoria’s Heritage Register. This will open a pop-up box with a thumbnail of each property and links to a more detailed description from the Victoria Heritage Foundation’s four-volume series This Old House, Victoria’s Heritage Neighbourhoods.

Although not covered in the Victoria Heritage Foundation’s This Old House series, Downtown commercial, industrial, institutional or apartment Heritage Register properties are included with links to their Statement of Significance on the Canadian Register of Historic Places, where available.

By William R. Muir

Drawings by Cecilia Mavrow

The primary purpose of a house is to provide shelter from the elements. But few homeowners are content with a building that just keeps them warm and dry; most want a home that is aesthetically attractive and that provides the viewer with a favourable impression of their social status. Throughout much of Victoria’s early history people have felt that a “styled” house, one whose shape, materials, detailing, or other features conform to a current architectural or social fashion, would do just that. Styles frequently begin when a creative architect devises an innovative house pattern that quickly catches local interest. It will spread when other architects consult the professional literature to keep current with national and international developments in building styles; professional builders often use pattern books of building plans that are currently popular.

Some styles have arisen from an attraction to buildings considered typical of a particular historical time and place. Ancient Greece and Rome, for example, have provided models for homebuilders during several periods, generally referred to as the Classical Revival Movement (“Revival” is used here to indicate that a style from an earlier era is being recreated). For some this was because of nostalgia for what was considered to be a superior way of life at that time, which might be emulated today by imitating its architecture. For others the buildings of that era were intrinsically attractive and needed no ideological justification for copying.

Other styles have emerged because a particular abstract preconception of attractiveness such as “symmetry” or “use of natural materials” has been generally agreed upon. Sometimes this type of style can coexist with or emerge from a historical style; for instance, one of the characteristics of Classical Revival houses is that they are usually symmetrical, and symmetry can remain a valued characteristic of a building long after people stop consciously copying Greek and Roman models.

However, the popularity of a particular style at a particular time has often been governed by factors other than aesthetics and domestic comfort; politics and ideology frequently played a role. This point will be further elaborated in the discussion of individual styles.

Folk or Vernacular

×

Not all houses are designed according to the latest mode. Some homes, typically built by their owners or by small-scale or nonprofessional builders, show little concern for changing fashions. The criterion for the choice of design of such houses is more likely to be the cost of construction or local architectural traditions. In this book houses that do not conform to a generally recognized style that occurs outside Victoria will be termed vernacular, or as a house form or type. Even so, these buildings have often obviously been influenced, directly or indirectly, by some conventional style. Vernacular buildings that contain some features associated with a standard style will be identified as such.

Colonial Bungalow / Classical Cottage

One house type frequently seen in Victoria that can be considered a vernacular style is the single-storey, hipped-roof cottage or bungalow. An important attraction it offers is economy: it provides the most space for the least money of any building shape. It has been suggested that this style was inspired by a building found by British colonial administrators in India called a bangla, resulting in its being named a Colonial Bungalow.

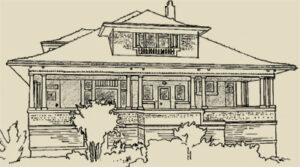

This 1½ storey, bellcast hipped-roof cottage built in 1911 at 614 Seaforth (Vic West) nicely demonstrates the basic features of the Colonial Bungalow. Many examples of this type have only attic space under the broad-eaved roof with a single dormer to light it, but this house was designed with second-storey living space, complete with generous dormer windows and a sleeping porch. A full-width front porch is sheltered under the house roof. The Tuscan Classical Revival columns supporting the porch are a sign of its being built in the Edwardian era.

There are other possibilities for the inspiration of single-storey, hipped-roof house-types in Victoria, such as similar houses observed in French North America or the Ontario Classical Cottage of the 19th Century. Classical Cottages generally have a smaller, more formal entry porch. They often have features borrowed from the dominant style of larger houses at the time they were built: the Italianate cottage typically has eaves brackets and a front angled bay window balancing the entry porch, both with hooded roofs, while if it has turned “gingerbread” porch supports and prominent, asymmetrically placed, pedimented bay windows it would be called a Queen Anne Cottage.

Classical Revival

×

Modern western civilization has long recognized that its roots lie in the cultures of classical Greece and Rome, and there have been several architectural movements based in some part upon emulating buildings of ancient times. Sometimes this has been manifested as a direct copying of Greek or Roman buildings. Other styles have been based on designing buildings according to the same rational principles used by classical architects, such as symmetry, balance, and proportion.

In addition to the specific styles it produced, the classical movement also contributed eclectic elements to other different styles. This was particularly the case in the period from around 1900 to 1914, when many houses became simpler and more symmetric, and made use of ornamental dentils and columns. This is sometimes referred to as the Edwardian Classical Revival.

Neoclassical Style

The World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, widely publicized several impressive buildings based on classical themes, and inspired many similar architect-designed buildings in the United States and (to a lesser extent) in Canada over the next half-century. Only a few examples of these are seen in relatively pure form in Victoria, mostly in commercial or institutional buildings. Typically there is a domination of the façade (and sometimes the sides) of the building by a porch that appears to have been taken from a Greek temple. Although the bulk of the building may obviously be a different style, it is usually symmetrical and may have classical details.

Neoclassical

This building at 1600 Quadra (North Park), designed as the First Congregational Church in 1913, is a symmetric brick building fronted by two-storey Ionic columns supporting a wide frieze and a triangular pediment. Classical details are the modillions under the eaves and dentils on the cornice, and the three triangular pediments above the entrance doors.

Homestead Style (Vernacular)

The first North American interest in classical buildings occurred from around 1770 to 1860, after the American Revolution when the republican concept of Rome fired the public imagination in the United States and suggested an architectural model, first for public buildings and then for homes. Well-known examples are the Gone with the Wind columned mansions built in the southern states before the Civil War. This was too early to directly affect developments in Victoria. However, numerous simpler vernacular approximations to these houses were subsequently built throughout North America, particularly in rural areas, and remained popular long after the demise of the formal style. The type ultimately became a favourite for inexpensive working-class houses built on narrow city lots. They are typically 1½ or two storeys tall, with a front-gabled roof and a porch that can be recognized as approximating the form of a Greek temple. For this reason they are also called Temple Houses.

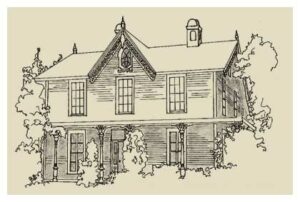

Homestead Style

It is doubtful that the builders of this 1892 house at 2011 Cameron (Fernwood) were thinking of a Greek temple when it was constructed, but its similarity to mid-19th-Century houses that were designed on classical models is clear. It is close to symmetric and has a modestly pitched front-gabled roof, in this case with an incomplete pediment and cornice returns. There is a board frieze under the eaves, while cornerboards represent pilasters. The porch even has three square supports approximating Corinthian columns with stylized fretwork foliage in the capitals.

Georgian Revival Style

Another architectural style based on principles of classicism was Georgian, which began as a favourite for British stately country homes. A few vernacular Georgian homes (for example, Craigflower Manor in View Royal) were built by pioneers in the Victoria area. However, the only surviving examples of the style within Victoria date from the beginning of the 20th Century, when it enjoyed a revival of interest that has continued to this day.

The original Georgian houses were designed by British architects influenced by the classical principles of balance, symmetry, and simplicity as they perceived them in Italian Renaissance buildings. The classic Georgian house is a simple, two-storey, rectangular box with a hipped or side-gabled roof, and door and windows symmetrically arranged on the front façade. It typically has five double-hung sash windows on the top floor, and a central door and four windows at the ground level. The front entrance is the focal point of the façade, drawing the eye by being the most elaborately decorated feature of the house, projecting forward in a gable, or being enclosed by a porch. There are often classical features such as columns, pediments, modillions, or dentils on the house.

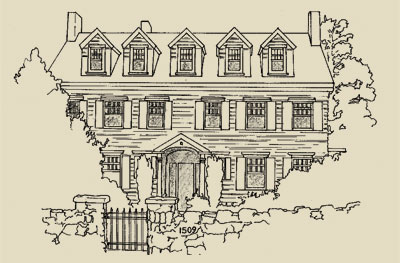

Georgian Revival

This Georgian Revival home at 1509 Rockland (Rockland) was built in 1922. Like most Revival houses it deviates somewhat from the original Georgian style: it has one window too many on the top floor. Apart from that it has many of the relevant features, such as symmetry, classical pediments on the dormers, and a door enclosed by a pedimented porch with classical columns. Most Georgian Revival houses in Victoria deviate even further from the norm with features such bay windows, multiple windows, and off-centre doors, not found on original Georgian models.

Romantic or Picturesque

×

Around the beginning of the 19th Century there was a reaction to the principles of Classicism, intellectual assumptions such as the appeal of simple symmetric structures determined by geometric rules. Instead, a new movement called Romanticism proposed aesthetic standards based on how buildings arouse emotional reactions in the observer (a similar development in music occurred when composers such as Tchaikovsky and Wagner moved away from the music of Bach). Such houses are often called Picturesque because their appearance was considered appropriate to be the subject of a painting. The Romantic or Picturesque styles were inspired by the architecture of particular historical periods, although they were often not very accurate copies of buildings of those times.

Gothic Revival Style

Gothic Revival

The first Canadian buildings in the Gothic Revival style were churches built at the beginning of the 19th Century, when it became considered as appropriate for religious and public buildings because of its associations with medieval European Christianity. It had earlier been used in England for grand country houses, and from there became popular for residences in the United States and Eastern Canada from about 1840 to 1865. Originally a style designed for masonry buildings, it was adapted to frame construction in a form called Carpenter Gothic for simpler homes. In Victoria it is mainly seen in churches and in residences originally built in country settings in the 1860s, although a few later examples can be found. Typical Gothic features are steeply gabled roofs with cross gables, elaborate carved bargeboards, flattened arches in porches, and pointed-arch windows (or rectangular windows with frame mouldings giving that effect) often extending into the gables.

Wentworth Villa was built at 1156 Fort (Fernwood) around 1862 in Carpenter Gothic. It is typical of how the Gothic style was applied to a modest residence with its steep side-gabled roof, centred wall-gable in the front façade, and intricately carved bargeboards. The wraparound porch with its support brackets simulating a flattened arch, and the token ornately detailed pointed window set prominently in the peak of the wall-gable, are examples of how an otherwise simple house could be transformed into a recognizable style.

Italianate Style

Houses based on Italian models were very popular in Victoria from 1860 to the turn of the 20th Century. Many of the first residences constructed on extensive estates outside town were inspired by the informal villas of the Italian countryside and were given the label “Italian Villa” style. These were rambling, two-storey structures, their low-pitched, gabled roofs frequently having widely overhanging eaves with decorative brackets beneath. They had tall, narrow windows with arched tops or hoods above them. The earliest examples had a prominent front-facing gable; a few later ones had a tower, almost always in the angle of two wings of the main building (rather than at a corner, as in Queen Anne houses).

Fairfield at 601 Trutch (Fairfield) was built in 1861 on an estate that would later become the neighbourhood of that name. It is a frame building, with rectangular windows topped by hoods, unlike the segmentally arched ones typically seen on stone or brick houses.

A second Italian house style that proved attractive in early Victoria was the Cubical Italianate. This was a severe, two-storey, symmetrical, box-shaped building with a hipped roof and bracketed eaves. The originals were always stone, brick, or stucco, and usually had arched windows, belt courses, and corner quoins.

Italianate Style

Built in 1860 (and demolished in the 1960s) on a country estate that was later subdivided to become the neighbourhood of the same name, Fernwood was a good example of Cubical Italianate. It had a simple entry porch with square supports and a flattened arch.

Although the Italian Villa and Cubical Italianate forms were easily distinguishable in the 1860s, subsequent builders frequently built houses that were a composite of the two types that became known simply as “Italianate style.” Houses with several wings had hipped roofs, 1- or 2-storey bay windows were often added, and Classical Revival features such as triangular pediments on gables became common. At the end of the 19th Century many simple box-like structures were made stylish just by the addition of some eaves gables and window hoods. To complicate things further, many builders of Queen Anne houses added Italianate features, so that assigning a single style becomes debatable for many houses.

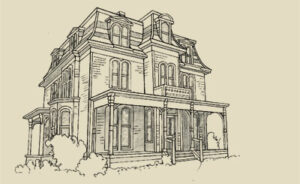

Second Empire (Mansard) Style

This style reached North American notice because of its part in the extensive building program undertaken during the reign of Napoleon III (1852-1870), France’s Second Empire. So although it had its origins in the French Renaissance, it was perceived at the time as being a modern and very up-to-date introduction, in contrast to the Romantic and historic nature of the revival styles. Perhaps for this reason it was short-lived – it was used in Victoria for four public buildings in the period 1875-1882 (the Customs House, City Hall, the Masonic Temple, and the now-demolished Central Boys School) and a handful of surviving residences built around 1890.

Second Empire

The distinguishing feature of Second Empire is its mansard (dual-pitched) hipped roof that changes from a steep to a shallow angle. The steep portion of the roof can be straight, or curved in complex ways, and typically will have dormer windows in it. The remainder of the house is usually very similar to an Italianate home. A classic example of a Second Empire house, Trebatha at 1124 Fort (Fernwood) was built in 1887. Its roof begins with a flare and then straightens, topped with a shallow hip. The rest of the building is indistinguishable from a Cubical Italianate house with its narrow double segmentally arched windows.

Queen Anne Style

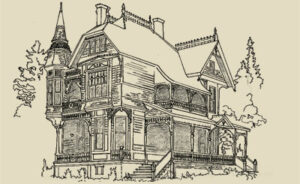

This style is the epitome of a Picturesque building style. Supposedly inspired by the architecture current during the reign of Queen Anne (1702 – 14), the concept was in fact created by a group of British architects in the 1860s working from late medieval models, which also provided inspiration for the Gothic and Tudor Revival styles and the Arts & Crafts movement. The first Queen Anne built in Victoria beginning in the 1880s represented this British school. But the style was modified south of the border to a more flamboyant architectural expression (typically with a wraparound entry porch decorated with spindlework), and the 1890s saw several still surviving homes built in a more North American mode. In Victoria the style was also frequently modified with Italianate elements, and in its dying days in the first decade of the 20th Century (Edwardian Era) Classical Revival features were often added.

This style was the antithesis of the simple, symmetric Classical approach. Victoria’s typical Queen Anne house has a steep hipped roof and two or more gables projecting irregularly, although a few are front-gabled. More elaborate dwellings will have a tower, usually octagonal or round, projecting from a front corner. The defining characteristic, however, of the style is its variety of surface treatments – a Queen Anne house will use almost anything to avoid a smooth-walled appearance: pent roofs, cutaway bay windows, projecting gables, half-timbering, patterned shingles, terracotta tiles in brickwork.

Roslyn (1135 Catherine, Vic West: drawing from photo courtesy CVA PR252-7098) also dates from 1890, but illustrates how the style had developed after being imported to the United States; this house was built from a mail-order plan by American architect G.F. Barber. On the porches it shows the feature most popularly associated with the Queen Anne style, spindlework. It also demonstrates many of the elements used to avoid flat wall surfaces: projecting gables, pent roofs, horizontal siding, and a variety of shingle patterns.

This is a picture of 223 Robert (Vic West), built in 1903-04. It has many typical features of the late Victorian Queen Anne style such as the fancy shingles and pent roof in the gables, the cutaway bay windows, and the Italianate brackets under the eaves. However, the beginning of the transition to the Edwardian period is marked by touches such as the discreet narrow beveled siding and Classical Revival features like the Tuscan columns on the porch. Smaller single- or 1½-storey versions are called Queen Anne cottages.

This style originated on the northeastern coast of the USA, principally in vacation residences in fashionable resorts, and inspired several Victoria homes and churches at the end of the 19th Century. The defining feature of a Shingle building is wall cladding of continuous wooden shingles, almost like a skin, which unifies the irregular shape of the house within a smooth surface. They often have substantial masonry foundations or ground floors. Their roofs are typically steep and may be gabled or hipped with cross-gables (like the Queen Anne), and like that style they are usually rambling, asymmetric buildings. They also frequently have corner towers, usually integrated bulgelike into the body of the house, rather than attached as distinct structures. The classic examples of the style emphasize the horizontal lines of the building, strips of multiple windows often contributing to this impression. Shingle buildings often also incorporate Romanesque arches and Classical Revival details such as Palladian windows.

This house built in 1896 at 1032 McGregor (Rockland) is based on what appears to be a rubble stone foundation, above which it rises like an irregular pile of simple geometric forms, all bound together by a shingled casing. Window surrounds have little decorative detail, and the continuity of the surface has minimal interruption from features such as corner boards and stringcourses. A multiple string of windows runs around the top of the tower and across the overhanging gable in an attempt to counteract the vertical impression given by the building’s sitting on the brow of a hill.

Arts & Crafts

×

This was not as much a style as an ideological movement, although the Victoria architects who were influenced by it left a recognizable mark upon the local landscape. The Arts & Crafts movement is most simply summarized as one initiated by a group of British artists and architects reacting to several features of Late Victorian life, principally the dehumanizing effects of industrialization and the unquestioning imitation of earlier formal historical styles. Rather, they espoused architecture that showed evidence of human handiwork, that was functional, and that respected British vernacular traditions of house building. Ironically, their admiration of the vernacular meant that they often incorporated elements from medieval buildings in their work that were also copied by the proponents of the Gothic, Queen Anne, and Tudor Revival styles that they criticized. As a result, it is sometimes difficult to discern the boundaries between these different styles.

Tudor Revival

Tudor Revival (also known as English or Elizabethan Revival) is a style that was created to evoke the spirit of traditional medieval English structures, particularly rambling country manor houses and rural cottages. The first examples were architect-designed stately homes in late-nineteenth century England that mimicked the appearance of growth through centuries of additions. Throughout the British Empire, and in Victoria in particular, this architectural style came to symbolize a traditional British way of life. There are a few instances in Victoria of homes similar to the original, historically inspired prototypes. However, most examples of the style here use it in eclectic mixtures. Many local architects (notably Samuel Maclure) used selected Tudor Revival elements in their designs, apparently to appeal to their clients’ Anglophile bents, but without attempting to create historically accurate copies. And a large number of more modest homes built in the first third of the twentieth century were modelled on medieval cottages in a subset of the style called English or Cotswold Cottage, which sometimes included an attempt to simulate a thatched roof.

Tudor Revival

The style is described here as a set of features frequently found in houses that are at least part Tudor Revival. The more features that appear in a given building, the closer it is to the style. Hatley Park, designed by Samuel Maclure, with Douglas James, and illustrated here, is possibly the purest version of Tudor Revival to be found in the Capital Region.

- steep, side-gabled roof

- one or more steeply pitched front gables, often asymmetric or overlapping

- decorative half-timbering inset with masonry (usually stucco) (This may also be found in the gables of Queen Anne and Arts & Crafts houses, which derive from medieval models as well. Half-timbered gables and walls usually indicate a Tudor Revival house.)

- entry with either no or a small porch, frequently with a flattened, pointed (Tudor) arch and quoin-like tabs of brick or stone projecting into the surrounding masonry

- oriel windows

- either rows of three or more casement windows, or tall narrow windows, often with multiple panes or leaded diamond glass

- jettied upper storeys (also indicative of Queen Anne and Arts & Crafts houses)

- massive chimneys on an outside wall, sometimes with multiple flues (This can be a feature distinguishing Tudor Revival from Queen Anne and other types of Arts & Crafts houses, whose chimneys are usually internal.)

- crenellated towers and bay windows

British Arts & Crafts

The British Arts & Crafts concept was attractive in Victoria to “Little England” enthusiasts intent on recreating the homeland on Canadian soil. A large number of architects with appropriate backgrounds were available to oblige by providing house designs in this genre for upmarket clients. As the British models they worked from were diverse, so were the Victoria houses they produced; as well, individual architects added their own idiosyncratic touches to their work. But there is a common mood to these houses: although they look like they have just been plucked, steep-roofed and asymmetrical, from the English countryside, they don’t look out of place in a British Columbian suburb, particularly in terms of their building materials.

Brothers Douglas and Percy Leonard James, both trained in England, designed 1015 Moss (Rockland; drawing from photo, 1977, Hallmark Society), built in 1912-13. It is clad largely in shingle, but features many medieval British features such as half-timbered panels, leaded-glass windows, and oriel window on the side. The prominent gable on the left of the façade, with its recessed arch and two-storey bay window, looks as though it has come from an earlier Queen Anne, but there is no variety-for-variety’s sake in this house: it has an overall unity to it.

Edwardian Vernacular Arts & Crafts

This vernacular house type with strong Arts & Crafts features, although not unique to Victoria, seems to have been built here in larger numbers than anywhere else. Thousands were constructed during an economic boom between 1904-1914; fewer can be traced to before or after that period. Most were built by contractors such as David Herbert Bale, and do not seem to have been architect-designed, although it has been suggested that some of the houses of renowned Victoria architect Samuel Maclure provided a model for them.

The basic characteristics of this house are a height of 1½ storeys, with the second level designed for living space, and a front-gabled roof pitched at approximately 45 degrees, with the gable ends at the top of the main floor walls. There are typically one or two dormers, usually gabled. Half-timbering and dentil mouldings are often seen in the gables, and many have wide bargeboards with eave returns at the bottom. Earlier instances typically have closed eaves; later ones may have open eaves and exposed rafter tails similar to those in Craftsman houses. Almost all have an asymmetrical main floor on the front facade, with inset entry porch on one side of the façade and a bay window on the other, and a symmetrical upper level.

The façade of 1127 Fort (Fairfield) built in 1907, is suggestive of a gable on a Queen Anne house (which is related to the Arts & Crafts movement) in its multiple levels and surface treatments. The half-timbered gable and prominent roofline are reminiscent of several high-fashion Arts & Crafts houses based on a Swiss Chalet model designed a few years earlier by Samuel Maclure.

Craftsman Style

The Arts & Crafts philosophy was taken up in the United States by furniture maker Gustav Stickley in his magazine The Craftsman, where he made available plans for houses in that fashion for free; the magazine name subsequently became identified with the American version of the style. Stickley stressed the use of low, broad proportions, natural building materials, and the absence of artificial ornamentation in his houses. Two California architects, brothers Charles and Henry Greene, popularized Craftsman-style bungalows, and shortly after 1905 the style and house type became the dominant one for smaller American houses until the early 1920s; in fact, the style is frequently referred to simply as “Bungalow.” Many companies sprang up to offer building plans, full kits of building materials that could be shipped to the customer’s lot, or complete design and construction services to erect a house in this style. Many Victoria Craftsman bungalows, two-storey houses, and even a few Craftsman churches date from this period.

Craftsman buildings tend to differ from British Arts & Crafts structures in having lower-pitched roofs. Their ornamentation, although its medieval origins are discernable, is more stylized; almost all Craftsmans have open eaves with exposed rafter tails, many have decorative beams or triangular braces under their gables, and local examples frequently have some token patches of half-timbering. They are usually side- or front-gabled, and have a front entry porch: in simple examples this will be incorporated under the main building roof, while more elaborate structures will have a gabled or shed-roofed porch in front. The porches on many Craftsmans have square supports based on battered stone piers or shingled balustrades. Bargeboards on gables are usually wide and frequently are slotted and have pointed tips.

Craftsman Style

This house was built in 1911 at 20-24 Douglas (drawing from photo c.1913 from Craftsman Bungalow catalogue, courtesy Larry Kreisman) from Plan 327 designed by architect Jud Yoho of Seattle. Massive stone pillars support the porch; more commonly in Craftsman houses the stone would extend only part way up as a pier, and wooden supports would rest on them. The open eaves, exposed raftertails, and beam-ends with brackets under the gables are typical.

Foursquare (Vernacular)

A group of Chicago architects, inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and known collectively as the Prairie School, originated a uniquely American house style at the beginning of the 20th Century. Many of these houses had low-pitched, hipped roofs with widely overhanging eaves, emphasizing horizontal lines. While this movement seems to have had minimal impact on professional architecture in Victoria, from houses scattered throughout the city there is ample evidence that builders, following their gut feelings on what clients wanted, were constructing scores of residences influenced by the style, presumably from the many pattern books available. Most date from shortly before WWI.

This house type is known as a Foursquare or Prairie Box. The basis of its appeal was in part functional – it is essentially a two-storey version of the Colonial Bungalow that had been an evergreen favourite for decades earlier because it was cheap to build. The introduction of platform frame construction would have decreased the cost of adding a second storey. In form it is also an expanded version of the Cubical Italianate that had been fashionable a generation earlier, minus the bay windows and eaves brackets, and plus some dormer windows on an expanded third level.

The classic Foursquare (so-called because it typically has four rooms on each level) is a hipped-roof cube with features that emphasize its horizontal lines: wide watertables, belt courses, and friezes separating levels of the building; contrasting materials at different levels; wide front porches; and multiple strings of windows. It usually has at least one dormer window.

Foursquare

This Foursquare at 123 Howe (Fairfield, not on City’s Heritage Registry) is a classic of the type. Its horizontality is accentuated by three bands of smooth boards girdling the house and separating the sections of rougher cladding, alternating claddings of shingle and bevelled siding, and contrasting colours for the different materials. All windows in the façade are in groups of three, there is a wide, low front porch, and the low front dormer further stresses the flattening effect of the bellcast roof.

By William R. Muir

Drawings by Cecilia Mavrow

The primary purpose of a house is to provide shelter from the elements. But few homeowners are content with a building that just keeps them warm and dry; most want a home that is aesthetically attractive and that provides the viewer with a favourable impression of their social status. Throughout much of Victoria’s early history people have felt that a “styled” house, one whose shape, materials, detailing, or other features conform to a current architectural or social fashion, would do just that. Styles frequently begin when a creative architect devises an innovative house pattern that quickly catches local interest. It will spread when other architects consult the professional literature to keep current with national and international developments in building styles; professional builders often use pattern books of building plans that are currently popular.

Some styles have arisen from an attraction to buildings considered typical of a particular historical time and place. Ancient Greece and Rome, for example, have provided models for homebuilders during several periods, generally referred to as the Classical Revival Movement (“Revival” is used here to indicate that a style from an earlier era is being recreated). For some this was because of nostalgia for what was considered to be a superior way of life at that time, which might be emulated today by imitating its architecture. For others the buildings of that era were intrinsically attractive and needed no ideological justification for copying.

Other styles have emerged because a particular abstract preconception of attractiveness such as “symmetry” or “use of natural materials” has been generally agreed upon. Sometimes this type of style can coexist with or emerge from a historical style; for instance, one of the characteristics of Classical Revival houses is that they are usually symmetrical, and symmetry can remain a valued characteristic of a building long after people stop consciously copying Greek and Roman models.

However, the popularity of a particular style at a particular time has often been governed by factors other than aesthetics and domestic comfort; politics and ideology frequently played a role. This point will be further elaborated in the discussion of individual styles.

Vernacular or Folk

Classical Revival

Romantic or Picturesque

Arts & Crafts

VERNACULAR or FOLK

Not all houses are designed according to the latest mode. Some homes, typically built by their owners or by small-scale or nonprofessional builders, show little concern for changing fashions. The criterion for the choice of design of such houses is more likely to be the cost of construction or local architectural traditions. In this book houses that do not conform to a generally recognized style that occurs outside Victoria will be termed vernacular, or as a house form or type. Even so, these buildings have often obviously been influenced, directly or indirectly, by some conventional style. Vernacular buildings that contain some features associated with a standard style will be identified as such.

Colonial Bungalow / Classical Cottage

One house type frequently seen in Victoria that can be considered a vernacular style is the single-storey, hipped-roof cottage or bungalow. An important attraction it offers is economy: it provides the most space for the least money of any building shape. It has been suggested that this style was inspired by a building found by British colonial administrators in India called a bangla, resulting in its being named a Colonial Bungalow.

Colonial Bungalow – 614 Seaforth

This 1½ storey, bellcast hipped-roof cottage built in 1911 at 614 Seaforth (Vic West) nicely demonstrates the basic features of the Colonial Bungalow. Many examples of this type have only attic space under the broad-eaved roof with a single dormer to light it, but this house was designed with second-storey living space, complete with generous dormer windows and a sleeping porch. A full-width front porch is sheltered under the house roof. The Tuscan Classical Revival columns supporting the porch are a sign of its being built in the Edwardian era.

There are other possibilities for the inspiration of single-storey, hipped-roof house-types in Victoria, such as similar houses observed in French North America or the Ontario Classical Cottage of the 19th Century. Classical Cottages generally have a smaller, more formal entry porch. They often have features borrowed from the dominant style of larger houses at the time they were built: the Italianate cottage typically has eaves brackets and a front angled bay window balancing the entry porch, both with hooded roofs, while if it has turned “gingerbread” porch supports and prominent, asymmetrically placed, pedimented bay windows it would be called a Queen Anne Cottage.

CLASSICAL REVIVAL STYLES

Modern western civilization has long recognized that its roots lie in the cultures of classical Greece and Rome, and there have been several architectural movements based in some part upon emulating buildings of ancient times. Sometimes this has been manifested as a direct copying of Greek or Roman buildings. Other styles have been based on designing buildings according to the same rational principles used by classical architects, such as symmetry, balance, and proportion.

In addition to the specific styles it produced, the classical movement also contributed eclectic elements to other different styles. This was particularly the case in the period from around 1900 to 1914, when many houses became simpler and more symmetric, and made use of ornamental dentils and columns. This is sometimes referred to as the Edwardian Classical Revival.

Neoclassical Style – 1600 Quadra St

Neoclassical Style

The World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, widely publicized severalimpressive buildings based on classicalthemes, and inspired many similar architect-designed buildings in the United States and (to a lesser extent) in Canada over the next half-century. Only a few examples ofthese are seen in relatively pure form in Victoria, mostly in commercial or institutional buildings. Typically there is a domination of the façade (and sometimes the sides) of the building by a porch that appears to have been taken from a Greek temple. Although the bulk of the building may obviously bea different style, it is usually symmetrical and may have classical details.

This building at 1600 Quadra (North Park), designed as the First Congregational Church in 1913, is a symmetric brick building fronted by two-storey Ionic columns supporting a wide frieze and a triangular pediment. Classicaldetails are the modillions under the eaves and dentils on the cornice, and the three triangular pediments above the entrance doors.

Homestead Style – 2011 Cameron St

Homestead Style (Vernacular)

The first North American interest in classical buildings occurred from around 1770 to 1860, after the American Revolution when the republican concept of Rome fired the public imagination in the United States and suggested an architectural model, first for public buildings and then for homes. Well-known examples are the Gone with the Wind columned mansions built in the southern states before the Civil War. This was too early to directly affect developments in Victoria. However, numerous simpler vernacular approximations to these houses were subsequently built throughout North America, particularly in rural areas, and remained popular long after the demise of the formal style. The type ultimately became a favourite for inexpensive working-class houses built on narrow city lots. They are typically 1½ or two storeys tall, with a front-gabled roof and a porch that can be recognized as approximating the form of a Greek temple. For this reason they are also called Temple Houses.

It is doubtful that the builders of this 1892 house at 2011 Cameron (Fernwood) were thinking of a Greek temple when it was constructed, but its similarity to mid-19th-Century houses that were designed on classical models is clear. It is close to symmetric and has a modestly pitched front-gabled roof, in this case with an incomplete pediment and cornice returns. There is a board frieze under the eaves, while cornerboards represent pilasters. The porch even has three square supports approximating Corinthian columns with stylized fretwork foliage in the capitals.

Georgian Revival Style

Another architectural style based on principles of classicism was Georgian, which began as a favourite for British stately country homes. A few vernacular Georgian homes (for example, Craigflower Manor in View Royal) were built by pioneers in the Victoria area. However, the only surviving examples of the style within Victoria date from the beginning of the 20th Century, when it enjoyed a revival of interest that has continued to this day.

Georgian Revival Style – 1509 Rockland

The original Georgian houses were designed by British architects influenced by the classical principles of balance, symmetry, and simplicity as they perceived them in Italian Renaissance buildings. The classic Georgian house is a simple, two-storey, rectangular box with a hipped or side-gabled roof, and door and windows symmetrically arranged on the front façade. It typically has five double-hung sash windows on the topfloor, and a central door and four windows at the ground level. The front entrance is the focal point of the façade, drawing the eye by being the most elaborately decorated feature of the house, projecting forward in a gable, or being enclosed by a porch. There are often classical features such as columns, pediments, modillions, or dentils on the house.

This Georgian Revival home at 1509 Rockland (Rockland) was built in 1922. Like most Revival houses it deviates somewhat from the original Georgian style: it has one window too many on the top floor. Apart from that it has many of the relevant features, such as symmetry, classical pediments on the dormers, and a door enclosed by a pedimented porch with classical columns. Most Georgian Revival houses in Victoria deviate even further from the norm with features such bay windows, multiple windows, and off-centre doors, not found on original Georgian models.

ROMANTIC or PICTURESQUE STYLES

Around the beginning of the 19th Century there was a reaction to the principles of Classicism, intellectual assumptions such as the appeal of simple symmetric structures determined by geometric rules. Instead, a new movement called Romanticism proposed aesthetic standards based on how buildings arouse emotional reactions in the observer (a similar development in music occurred when composers such as Tchaikovsky and Wagner moved away from the music of Bach). Such houses are often called Picturesque because their appearance was considered appropriate to be the subject of a painting. The Romantic or Picturesque styles were inspired by the architecture of particular historical periods, although they were often not very accurate copies of buildings of those times.

Gothic Revival Style

The first Canadian buildings in the Gothic Revival style were churches built at the beginning of the 19th Century, when it became considered as appropriate for religious and public buildings because of its associations with medieval European Christianity. It had earlier been used in England for grand country houses, and from there became popular for residences in the United States and Eastern Canada from about 1840 to 1865. Originally a style designed for masonry buildings, it was adapted to frame construction in a form called Carpenter Gothic for simpler homes. In Victoria it is mainly  seen in churches and in residences originally built in country settings in the 1860s, although a few later examples can be found. Typical Gothic features are steeply gabled roofs with cross gables, elaborate carved bargeboards, flattened arches in porches, and pointed-arch windows (or rectangular windows with frame mouldings giving that effect) often extending into the gables.

seen in churches and in residences originally built in country settings in the 1860s, although a few later examples can be found. Typical Gothic features are steeply gabled roofs with cross gables, elaborate carved bargeboards, flattened arches in porches, and pointed-arch windows (or rectangular windows with frame mouldings giving that effect) often extending into the gables.

Wentworth Villa was built at 1156 Fort (Fernwood) around 1862 in Carpenter Gothic. It is typical of how the Gothic style was applied to a modest residence with its steep side-gabled roof, centred wall-gable in the front façade, and intricately carved bargeboards. The wraparound porch with its support brackets simulating a flattened arch, and the token ornately detailed pointed window set prominently in the peak of the wall-gable, are examples of how an otherwise simple house could be transformed into a recognizable style.

Italianate Style

Houses based on Italian models were very popular in Victoria from 1860 to the turn of the 20th Century. Many of the first residences constructed on extensive estates outside town were inspired by the informal villas of the Italian countryside and were given the label “Italian Villa” style. These were rambling, two-storey structures, their low-pitched, gabled roofs frequently having widely overhanging eaves with decorative brackets  beneath. They had tall, narrow windows with arched tops or hoods above them. The earliest examples had a prominent front-facing gable; a few later ones had a tower, almost always in the angle of two wings of the main building (rather than at a corner, as in Queen Anne houses).

beneath. They had tall, narrow windows with arched tops or hoods above them. The earliest examples had a prominent front-facing gable; a few later ones had a tower, almost always in the angle of two wings of the main building (rather than at a corner, as in Queen Anne houses).

Fairfield at 601 Trutch (Fairfield) was built in 1861 on an estate that would later become the neighbourhood of that name. It is a frame building, with rectangular windows topped by hoods, unlike the segmentally arched ones typically seen on stone or brick houses.

A second Italian house style that proved attractive in early Victoria was the Cubical Italianate. This was a severe, two-storey, symmetrical, box-shaped building with a hipped roof and bracketed eaves. The originals were always stone, brick, or stucco, and usually had arched windows, belt courses, and corner quoins.

Italianate Style

Built in 1860 (and demolished in the 1960s) on a country estate that was later subdivided to become the neighbourhood of the same name, Fernwood was a good

example of Cubical Italianate. It had a simple entry porch with square supports and a flattened arch.

Although the Italian Villa and Cubical Italianate forms were easily distinguishable in the 1860s, subsequent builders frequently built houses that were a composite of the two types that became known simply as “Italianate style.” Houses with several wings had hipped roofs, 1- or 2-storey bay windows were often added, and Classical Revival features such as triangular pediments on gables became common. At the end of the 19th Century many simple box-like structures were made stylish just by the addition of some eaves gables and window hoods. To complicate things further, many builders of Queen Anne houses added Italianate features, so that assigning a single style becomes debatable for many houses.

Second Empire (Mansard) Style

This style reached North American notice because of its part in the extensive building program undertaken during the reign of Napoleon III (1852-1870), France’s Second Empire. So although it had its origins in the French Renaissance, it was perceived at the time as being a modern and very up-to-date introduction, in contrast to the Romantic and historic nature of the revival styles. Perhaps for this reason it was short-lived – it was used in Victoria for four public buildings in the period 1875-1882 (the Customs House, City Hall, the Masonic Temple, and the now-demolished Central Boys School) and a handful of surviving residences built around 1890.

The distinguishing feature of Second Empire is its mansard (dual-pitched) hipped roof that changes from a steep to a shallow angle. The steep portion of the roof can be straight, or curved in complex ways, and typically will have dormer windows in it. The remainder of the house is usually very similar to an Italianate home. A classic example of a Second Empire house, Trebatha at 1124 Fort (Fernwood) was built in 1887. Its roof begins with a flare and then straightens, topped with a shallow hip. The rest of the building is indistinguishable from a Cubical Italianate house with its narrow double segmentally arched windows.

The distinguishing feature of Second Empire is its mansard (dual-pitched) hipped roof that changes from a steep to a shallow angle. The steep portion of the roof can be straight, or curved in complex ways, and typically will have dormer windows in it. The remainder of the house is usually very similar to an Italianate home. A classic example of a Second Empire house, Trebatha at 1124 Fort (Fernwood) was built in 1887. Its roof begins with a flare and then straightens, topped with a shallow hip. The rest of the building is indistinguishable from a Cubical Italianate house with its narrow double segmentally arched windows.

Queen Anne Style

This style is the epitome of a Picturesque building style. Supposedly inspired by the architecture current during the reign of Queen Anne (1702 – 14), the concept was in fact created by a group of British architects in the 1860s working from late medieval models, which also provided inspiration for the Gothic and Tudor Revival styles and the Arts & Crafts movement. The first Queen Anne built in Victoria beginning in the 1880s represented this British school. But the style was modified south of the border to a more flamboyant architectural expression (typically with a wraparound entry porch decorated with spindlework), and the 1890s saw several still surviving homes built in a more North American mode. In Victoria the style was also frequently modified with Italianate elements, and in its dying days in the first decade of the 20th Century (Edwardian Era) Classical Revival features were often added.

This style was the antithesis of the simple, symmetric Classical approach. Victoria’s typical Queen Anne house has a steep hipped roof and two or more gables projecting irregularly, although a few are front-gabled. More elaborate dwellings will have a tower, usually octagonal or round, projecting from a front corner. The defining characteristic, however, of the style is its variety of surface treatments – a Queen Anne house will use almost anything to avoid a smooth-walled appearance: pent roofs, cutaway bay windows, projecting gables, half-timbering, patterned shingles, terracotta tiles in brickwork.

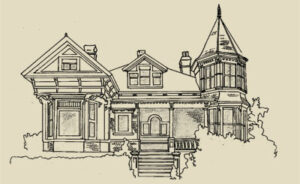

Roslyn (1135 Catherine, Vic West: drawing from photo courtesy CVA PR252-7098) also dates from 1890, but illustrates how the style had developed after being imported to the United States; this house was built from a mail-order plan by American architect G.F. Barber. On the porches it shows the feature most popularly associated with the Queen Anne style, spindlework. It also demonstrates many of the elements used to avoid flat wall surfaces: projecting gables, pent roofs, horizontal siding, and a variety of shingle patterns.

Roslyn (1135 Catherine, Vic West: drawing from photo courtesy CVA PR252-7098) also dates from 1890, but illustrates how the style had developed after being imported to the United States; this house was built from a mail-order plan by American architect G.F. Barber. On the porches it shows the feature most popularly associated with the Queen Anne style, spindlework. It also demonstrates many of the elements used to avoid flat wall surfaces: projecting gables, pent roofs, horizontal siding, and a variety of shingle patterns.

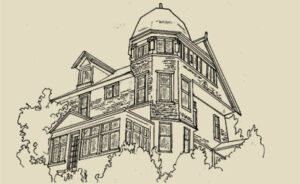

This is a picture of 223 Robert (Vic West), built in 1903-04. It has many typical features of the late Victorian Queen Anne style such as the fancy shingles and pent roof in the gables, the cutaway bay windows, and the Italianate brackets under the eaves. However, the beginning of the transition to the Edwardian period is marked by touches such as the discreet narrow beveled siding and Classical Revival features like the Tuscan columns on the porch. Smaller single- or 1½-storey versions are called Queen Anne cottages.

This is a picture of 223 Robert (Vic West), built in 1903-04. It has many typical features of the late Victorian Queen Anne style such as the fancy shingles and pent roof in the gables, the cutaway bay windows, and the Italianate brackets under the eaves. However, the beginning of the transition to the Edwardian period is marked by touches such as the discreet narrow beveled siding and Classical Revival features like the Tuscan columns on the porch. Smaller single- or 1½-storey versions are called Queen Anne cottages.

Shingle Style

This style originated on the northeastern coast of the USA, principally in vacation residences in fashionable resorts, and inspired several Victoria homes and churches at the end of the 19th Century. The defining feature of a Shingle building is wall cladding of continuous wooden shingles, almost like a skin, which unifies the irregular shape of the house within a smooth surface. They often have substantial masonry foundations or ground floors. Their roofs are typically steep and may be gabled or hipped with cross-gables (like the Queen Anne), and like that style they are usually rambling, asymmetric buildings. They also frequently have corner towers, usually integrated bulgelike into the body of the house, rather than attached as distinct structures. The classic examples of the style emphasize the horizontal lines of the building, strips of multiple windows often contributing to this impression. Shingle buildings often also incorporate Romanesque arches and Classical Revival details such as Palladian windows.

This house built in 1896 at 1032 McGregor (Rockland) is based on what appears to be a rubble stone foundation, above which it rises like an irregular pile of simple geometric forms, all bound together by a shingled casing. Window surrounds have little decorative detail, and the continuity of the surface has minimal interruption from features such as corner boards and stringcourses. A multiple string of windows runs around the top of the tower and across the overhanging gable in an attempt to counteract the vertical impression given by the building’s sitting on the brow of a hill.

This house built in 1896 at 1032 McGregor (Rockland) is based on what appears to be a rubble stone foundation, above which it rises like an irregular pile of simple geometric forms, all bound together by a shingled casing. Window surrounds have little decorative detail, and the continuity of the surface has minimal interruption from features such as corner boards and stringcourses. A multiple string of windows runs around the top of the tower and across the overhanging gable in an attempt to counteract the vertical impression given by the building’s sitting on the brow of a hill.

×

This was not as much a style as an ideological movement, although the Victoria architects who were influenced by it left a recognizable mark upon the local landscape. The Arts & Crafts movement is most simply summarized as one initiated by a group of British artists and architects reacting to several features of Late Victorian life, principally the dehumanizing effects of industrialization and the unquestioning imitation of earlier formal historical styles. Rather, they espoused architecture that showed evidence of human handiwork, that was functional, and that respected British vernacular traditions of house building. Ironically, their admiration of the vernacular meant that they often incorporated elements from medieval buildings in their work that were also copied by the proponents of the Gothic, Queen Anne, and Tudor Revival styles that they criticized. As a result, it is sometimes difficult to discern the boundaries between these different styles.

Tudor Revival

Tudor Revival (also known as English or Elizabethan Revival) is a style that was created to evoke the spirit of traditional medieval English structures, particularly rambling country manor houses and rural cottages. The first examples were architect-designed stately homes in late-nineteenth century England that mimicked the appearance of growth through centuries of additions. Throughout the British Empire, and in Victoria in particular, this architectural style came to symbolize a traditional British way of life. There are a few instances in Victoria of homes similar to the original, historically inspired prototypes. However, most examples of the style here use it in eclectic mixtures. Many local architects (notably Samuel Maclure) used selected Tudor Revival elements in their designs, apparently to appeal to their clients’ Anglophile bents, but without attempting to create historically accurate copies. And a large number of more modest homes built in the first third of the twentieth century were modelled on medieval cottages in a subset of the style called English or Cotswold Cottage, which sometimes included an attempt to simulate a thatched roof.

Tudor Revival

The style is described here as a set of features frequently found in houses that are at least part Tudor Revival. The more features that appear in a given building, the closer it is to the style. Hatley Park, designed by Samuel Maclure, with Douglas James, and illustrated here, is possibly the purest version of Tudor Revival to be found in the Capital Region.

- steep, side-gabled roof

- one or more steeply pitched front gables, often asymmetric or overlapping

- decorative half-timbering inset with masonry (usually stucco) (This may also be found in the gables of Queen Anne and Arts & Crafts houses, which derive from medieval models as well. Half-timbered gables and walls usually indicate a Tudor Revival house.)

- entry with either no or a small porch, frequently with a flattened, pointed (Tudor) arch and quoin-like tabs of brick or stone projecting into the surrounding masonry

- oriel windows

- either rows of three or more casement windows, or tall narrow windows, often with multiple panes or leaded diamond glass

- jettied upper storeys (also indicative of Queen Anne and Arts & Crafts houses)

- massive chimneys on an outside wall, sometimes with multiple flues (This can be a feature distinguishing Tudor Revival from Queen Anne and other types of Arts & Crafts houses, whose chimneys are usually internal.)

- crenellated towers and bay windows

British Arts & Crafts

The British Arts & Crafts concept was attractive in Victoria to “Little England” enthusiasts intent on recreating the homeland on Canadian soil. A large number of architects with appropriate backgrounds were available to oblige by providing house designs in this genre for upmarket clients. As the British models they worked from were diverse, so were the Victoria houses they produced; as well, individual architects added their own idiosyncratic touches to their work. But there is a common mood to these houses: although they look like they have just been plucked, steep-roofed and asymmetrical, from the English countryside, they don’t look out of place in a British Columbian suburb, particularly in terms of their building materials.

Brothers Douglas and Percy Leonard James, both trained in England, designed 1015 Moss (Rockland; drawing from photo, 1977, Hallmark Society), built in 1912-13. It is clad largely in shingle, but features many medieval British features such as half-timbered panels, leaded-glass windows, and oriel window on the side. The prominent gable on the left of the façade, with its recessed arch and two-storey bay window, looks as though it has come from an earlier Queen Anne, but there is no variety-for-variety’s sake in this house: it has an overall unity to it.

Edwardian Vernacular Arts & Crafts

This vernacular house type with strong Arts & Crafts features, although not unique to Victoria, seems to have been built here in larger numbers than anywhere else. Thousands were constructed during an economic boom between 1904-1914; fewer can be traced to before or after that period. Most were built by contractors such as David Herbert Bale, and do not seem to have been architect-designed, although it has been suggested that some of the houses of renowned Victoria architect Samuel Maclure provided a model for them.

The basic characteristics of this house are a height of 1½ storeys, with the second level designed for living space, and a front-gabled roof pitched at approximately 45 degrees, with the gable ends at the top of the main floor walls. There are typically one or two dormers, usually gabled. Half-timbering and dentil mouldings are often seen in the gables, and many have wide bargeboards with eave returns at the bottom. Earlier instances typically have closed eaves; later ones may have open eaves and exposed rafter tails similar to those in Craftsman houses. Almost all have an asymmetrical main floor on the front facade, with inset entry porch on one side of the façade and a bay window on the other, and a symmetrical upper level.